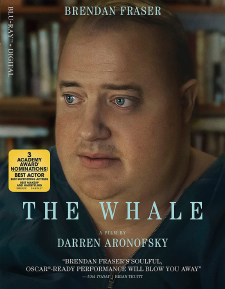

Whale, The (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Darren AronofskyRelease Date(s)

2022 (March 14, 2023)Studio(s)

Protozoa Pictures/A24 (Lionsgate)- Film/Program Grade: B

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: B-

Review

Actors have been known to change their appearance dramatically for a film role. Charlize Theron (Monster), Christian Bale (The Machinist), Jared Leto (Dallas Buyers Club), and Robert De Niro (Raging Bull) come to mind. Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale, based on a play and subsequent screenplay by Samuel D. Hunter, features an amazing physical transformation of an actor into a character.

Charlie (Brendan Fraser) is a middle-aged English teacher who deals with regret, despair, and self-destructiveness by overeating to the point of pathological obesity. Barely able to move and ashamed for other people to see his immense body, he isolates himself to his perpetually darkened apartment. He conducts his classes on Zoom and keeps the instructor box blank so that his students can’t see him. His gargantuan size is placing him in imminent danger of suffering a fatal heart attack.

Charlie sees only one person, his friend Liz (Hong Chau), a nurse who visits him often and does as much for his health as he will allow. Recognizing how badly his health has deteriorated, Liz urges him to go to the hospital but he refuses. Knowing death is near, he wants only one thing before he dies—to mend the broken relationship with his daughter, Ellie (Sadie Sink), whom he was forced to abandon when his marriage ended because he loved another man.

Liz is a compassionate woman who’s both empathetic to Charlie’s condition and angry with him for being unwilling to get the hospital care he needs. Though fatigued from her efforts to keep him alive, she remains a steady presence in his life as the bond between them becomes increasingly strained by his resistance. Without Liz’s help, Charlie would be dead already. He’s incapable of the most basic activities and can’t even lift himself off the couch, get into bed, or answer the door without heaving himself onto a walker. Later, as his health gets progressively worse, Liz brings him a wheelchair large enough to accommodate his huge bulk. For Charlie, standing is extremely difficult, walking nearly impossible, stepping into the light of day out of the question.

A young evangelical missionary, Thomas (Ty Simpkins), happens to arrive just as Charlie is having his first heart attack. Thrown into this crisis, Thomas does what he can to help until Liz arrives and takes charge. Later Ellie arrives, clearly disgusted and furious with her absent father. To keep her around for a while, Charlie offers her a large amount of money to inherit when he dies, which, he tells her, will be soon. This carrot tempts Ellie to stay, giving Charlie a chance to explain how sorry he was to leave her. Charlie says “I’m sorry” often, to everyone in his life.

The interplay among Charlie, Liz, and Thomas offers insight into all three characters as the knowledge that Charlie is fighting the clock to gain redemption creates suspense. How these three relate to one another is eventually revealed.

Charlie’s ex-wife Mary (Samantha Morton) appears late in the film and confronts Charlie for his apparently sudden interest in repairing a badly-damaged relationship with Ellie. Mary, of course, has also been abandoned and left to raise Ellie by herself. Morton conveys a combination of indignation, confusion, and motherly protectiveness.

Fraser brings a tender quality to Charlie along with the character’s self-destructive inclination, indelibly illustrated when he gorges on food—his way of hastening his demise. Wearing elaborate body and facial prosthetics, Fraser makes Charlie a real person rather than a circus freak. Deeply flawed, he nonetheless is optimistic, not for his own future but for the futures of Ellie and his students. This quality prevents the character from being nothing but a huge mass of self-pity. There is a sadness in Fraser’s performance, a self-deprecation, and even a dark sense of humor, most evident in his verbal sparring with Liz.

Sink portrays Ellie on a single note of victimization. Angry and petulant, she accuses, shouts, storms out, insults, and makes cruel comments. This delivery renders Ellie rather obnoxious. Though it keeps sympathy on the side of Charlie, her performance becomes irritating because of its one-note histrionics. Late in the film her icy, intractable veneer gives way when she becomes able to empathize with Charlie’s pain, physical but mostly emotional. The shift is so abrupt, however, that it comes off as inauthentic.

Director Aronofsky and screenwriter Hunter have not “opened up” the play, as is typical in film adaptations, since Charlie’s world is limited to his apartment and mostly to his couch. Aronofsky uses tracking shots to make compositions interesting and has the supporting characters in nearly constant motion, so we see the same set from many different points of view. Touches such as the gripper Charlie uses to reach items because he can no longer bend or stretch, the chain and grip bar he needs to get into and out of bed, and the placement of necessary objects well within his reach underscore his near immobility.

Aronofsky challenges viewers to see beyond pre-programmed ideas and biases to the beauty in Charlie, in the cadence of his voice, in his poetic soul. Camera angles emphasize Charlie’s heft and how cumbersome simply getting through an ordinary day is for him. With no flashback scenes of Charlie’s lover, it’s left to Fraser to convey that Alan was the true love of his life, but we learn more about their relationship from Liz than from Charlie himself. The film depicts a group of individuals who are all adrift and whose emotions waiver among anger, shame, and regret.

The Whale was captured digitally by director of photography Matthew Libatique in X-OCN ST (6K) quality using Sony CineAlta Venice cameras and Angenieux Optima Primo lenses, and finished as a 4K Digital Intermediate at the aspect ratio of 1.33:1. Lionsgate presents the film on Blu-ray. The color palette is desaturated, with bold colors rare. The only time we see red is in a commercial on Charlie’s TV. Charlie’s apartment is seen through slightly soft focus creating a murky greenish haze, suggesting a sense of sadness and regret. This gives a faded look, suggesting that Charlie’s life is waning. Tracking is used frequently to avoid static compositions, and there are no fancy camera shots that draw attention to themselves. The time of day is suggested by the quantity of light filtering in through window blinds. The comings and goings of people are seen through the blinds. In early scenes, the general lighting is dim, provided by lamps, with rain preventing much sun from shining into the apartment. Later, the room brightens as Charlie comes to terms with Ellie, his past, and his future.

The soundtrack is English 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio. English SDH and Spanish subtitles are available options. Dialogue is clear and distinct. Charlie’s speech is somewhat labored because of his difficulty breathing. He wheezes and coughs frequently. Ellie’s tone is almost always at fever pitch, while Thomas is soft spoken and never given to emotional outbursts. Mary’s dialogue is modulated between politeness and long-festering resentment. In one scene, when Charlie attempts to stand, a close-up shows his huge foot hitting the ground with a huge thud. Subtle sounds include Charlie uncomfortably shifting the position of his ungainly body. Rob Simonsen’s score creates the appropriate atmosphere without being too intrusive, subtly matching Charlie’s changing moods and creating a sense of nostalgic loss.

Lionsgate’s Blu-ray release includes a Digital Code included on a paper insert within the package. Bonus materials include the following:

- People Are Amazing: Making The Whale (24:33)

- The Sounds of the Sea: Scoring The Whale (7:41)

- Everything Everywhere All at Once Trailer (5:15)

- The Inspection Trailer (5:15)

People Are Amazing: Making The Whale – Writer Samuel D. Hunter notes that the genesis of The Whale harks back to a time in his past when he was in a state of depression and had gained weight. Director Darren Aronofsky had to “figure out the visual vocabulary” of the film. He couldn’t find an actor suitable to play Charlie until saw Brendan Fraser in a small role in another film. “Brendan had that bright light.” Fraser was drawn to the character because he saw in Charlie something heroic. “I was absolutely hooked and I wanted in.” Charlie is optimistic because he sees promise in others. The film’s stylization emerged from the set’s limited parameters. Sadie Sink discusses how methodically the shots were blocked. Aronofsky used older styles of filmmaking, including relying on tracking shots. Hong Chau and Ty Simpkins talk about their characters. Aronofsky’s style allowed for “a wealth of material you can take back to the editing room.” As the film progresses, it takes a journey from dark to light, visually and thematically noting faith in the goodness of human beings.

The Sounds of the Sea: Scoring The Whale – Composer Rob Simonsen discusses writing the music for The Whale. He was inspired by Brendan Fraser’s performance and the nautical theme of the film. Emotions can have depth, like the ocean. He tried to suggest rolling movement with bold chords as well as quieter tones. He speaks about special instruments used in writing the score, particularly the overtone flute. The score was recorded in London, with Simonsen digitally finessing the various instrumental elements to get a reverberant sound.

The Whale touches on parental responsibility, sexuality, religious homophobia, and the value of life. Fraser turns in a compelling performance, bringing sincerity, gentleness, and candidness to Charlie. The film is more a character study than a typical narrative, its origins as a play evident in the limited location and dramatic entrances and exits. The screenplay avoids simple soap opera, with well-written dialogue, atypical central character, and first-rate direction.

- Dennis Seuling