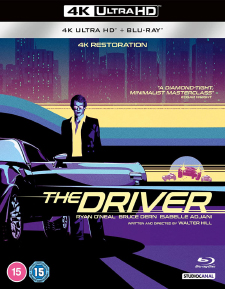

Driver, The (4K UHD Review)

Director

Walter HillRelease Date(s)

1978 (December 16, 2022)Studio(s)

EMI Films/20th Century Fox (StudioCanal)- Film/Program Grade: A-

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: B+

- Extras Grade: B-

Review

If Extreme Prejudice is Maximum Walter Hill, with everything dialed up to 11, then The Driver is Minimalist Walter Hill, with everything stripped down to the absolute bare essentials. It runs a lean, mean 91 minutes, with not an ounce of wasted fat on its already slender bones. The dialogue is sparse (the titular Driver notoriously speaks just 350 words in the entire film), the streets are deserted, the sets are austere, and the characterizations are deliberately wafer-thin. Hill’s script didn’t even bother to provide names for any of these characters—they’re all broad types, so he openly identified them as such. Ryan O’Neal is called The Driver, Bruce Dern is The Detective, Isabelle Adjani is The Player, and Ronee Blakely is The Connection. Instead of having names that might humanize them, they’re only described by the function that they serve in the relatively straightforward narrative—and the story itself little more than a framework on which to hang three extended car chases.

It all could have easily been standard cops and robbers fare, but Hill’s big twist (at producer Lawrence Gordon’s suggestion) was to focus on the getaway driver, rather than the robbers themselves. The whole film is basically a cat and mouse game between The Driver and The Detective, with the former just trying to make a living in his own singular fashion, and the latter trying to stop him from doing so by any means necessary. The Player and The Connection are simply caught in the middle of that duality. Hill’s secondary twist was that he didn’t really take sides in the conflict—there’s no protagonist in The Driver, just two diametrically opposed antagonists. The Detective doesn’t stand on any kind of moral high ground relative to The Driver, and the latter’s criminal activities are offset (in the Hawksian sense) by his superior professionalism. That balances the scales between the two of them, and if neither one of them is particularly heroic, then they both deserve each other. As Hill explained in 1978: “There are many people who break the law. (The Detective) catches them and puts them in jail, but they’re not special. He’s decided that The Driver is a special person, and he conceives of himself as being a very special person, and decides that he’s gonna bring him down.”

Bruce Dern is always going to Bruce Dern, so he was the perfect choice to play a morally ambiguous cop like this. On the other hand, casting O’Neal as a cold-blooded professional criminal has always been a far more controversial decision. Hill initially developed the project with Steve McQueen in mind, but despite the fact that they had previously worked together in different capacities on The Getaway, The Thomas Crown Affair, and Bullitt, McQueen decided that he had done enough car films at that stage of his career. Hill’s Hard Times lead Charles Bronson also turned it down, since the two had a bit of a falling out over the final editing of that film. Ryan O’Neal was a reliable box office draw at that point, but he was hardly anyone’s first choice for this kind of project. While he did receive a fair amount of criticism in 1978, that’s partly due to the fact that the role was such a departure for him, and it’s hard for people to accept familiar actors playing against type. Yet with the benefit of hindsight, he’s every bit the equal of Dern in the film. There was always an impassiveness to O’Neal’s face that works perfectly for The Driver; McQueen’s innate charm would have actually worked against the effectiveness of the character. The Driver doesn’t really have a personality, just a job, and that’s why O’Neal’s inherent stoniness matches the minimalistic style that Hill brought to the film.

That minimalism extends to the car chases that are the centerpiece of The Driver, and they’re refreshingly free of the wretched excess that mars most modern car chases. Everything is clean, clear, and comprehensible, with none of the quick cutting or shaky camerawork that’s so prevalent today. As staged by stunt coordinator Everett Creach, the action is straightforward, and while there’s an occasional concession to Hollywood convention, such as hidden ramp rollovers, the chases are still generally plausible. It’s all visually compelling, too, thanks to the use of muscular cars and trucks in all of the scenes. That’s one lesson from Bullitt, The French Connection, and To Live and Die in L.A. that tends to be lost on contemporary filmmakers. Sleeker sports cars may look more imposing in real life, but they tend not to have the same kind of impact on screen. The fanciest major vehicle in The Driver is a 1970 Mercedes-Benz 280S that’s quickly dispatched and never seen again. The rest of the film offers a less expensive but more imposing collection that includes a 1970 Ford Galaxie 500, a 1976 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am, and a 1973 Chevrolet C-10 Stepside pickup truck. Even the police are driving 1974 Plymouth Furies as patrol cars. As a result, everything feels like it has real weight and mass, which adds to the dynamics of any given scene. It’s also worth noting that O’Neal did some of his own stunt driving, which adds to the verisimilitude of the action, and further proves that he was a worthy replacement for McQueen.

Walter Hill has worked in a variety of genres over the decades, but he’s really always been a genre unto himself regardless of the specific stories that he may be telling. The presence of hot actors like Eddie Murphy has turned films like 48 Hours into sizable hits, but for the most part, the real draw of a Walter Hill film is just that: Walter Hill. That’s limited their box office potential, and despite the presence of Ryan O’Neal in the lead role, The Driver was a financial disappointment in 1978. Yet like many other films that he’s directed, it’s risen from the ashes of box office failure to become recognized as a cult classic today. That’s not a bad legacy for one of the most iconic filmmakers from the last few decades of American cinema. When many of the big box office hits have long been forgotten, films like The Driver will continue to be remembered for decades to come.

Cinematographer Philip Lathrop shot The Driver on 35 mm film using Panavision Panaflex cameras with spherical lenses, framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. For this new version, the original camera negative was scanned at 4K resolution and restored by Colorworks, with Walter Hill supervising the process. Final High Dynamic Range grading and authoring was performed at Roundabout L.A., in conjunction with StudioCanal. (Both Dolby Vision and HDR10 are included on the disc.) The Driver has always been an understated, almost drab-looking film, so the results aren’t spectacular in the sense of providing conventional eye candy, but this is still an extraordinarily accurate representation of textures of the film medium itself. Everything is spotless and immaculately clean, but the grain remains intact and looks completely natural at all times—StudioCanal has had a spotty record when it comes to encodes, but this one is nearly perfect. There’s a decent amount of fine detail on display, though there was only so much actual detail on the negative to begin with. The optically printed opening titles are naturally a bit softer, but far less distractingly so than most other films of the era.

The HDR grade enhances the original look without revising it—the highlights aren’t necessarily brighter, but the contrast is slightly stronger during the nighttime driving scenes, with nicely accentuated halation around the light sources like street lamps to make them really stand out from the deep blacks in the background. The colors are generally muted, with occasional burst of red such as with Ronee Blakely’s lipstick or that memorable C-10 pickup truck in the finale, but while those are richer here than on Blu-ray, they’re not necessarily more vivid. Aside from a few intentional effects like that, the overall cooler color scheme is reproduced accurately in this grade—for a film as cool as The Driver, with a lead character who is just as cool and composed, the colors need to match that coolness. This may not be demo material for anyone who wants to show off the extreme detail, color, or contrast that the UHD format can provide, but for anyone with a lifelong love of the film medium, it’s eye candy of a different sort. This is a purely digital presentation that still looks authentically like film, and that’s no small matter.

Audio is offered in English, French, and German 2.0 mono LPCM, with optional English SDH, French, and German subtitles. The audio is as clean as the video, with no noise, hiss, or any other artifacts to report. There’s not much in the way of dynamics, but there never has been in any previous version, so that’s just how it was mixed. The dialogue is clear, though some of the ADR integrates awkwardly, but again, that’s how it was recorded and mixed. The minimalistic score was by Michael Small, who was a bit of one-man cottage industry in the Seventies providing exactly this kind of understated support for thrillers like The Stepford Wives, The Parallax View, Night Moves, and Marathon Man. He was the musical patron poet of paranoia, and his score helps maintain that same kind of atmosphere for The Driver.

StudioCanal’s 4K Ultra HD release of The Driver is a two-disc set that includes a Region B-locked Blu-ray with a 1080p copy of the film (a Steelbook option is also available). The extras are duplicated on both discs, and they’re all in 4K with SDR on the UHD, but note that only the Alternate Opening appears to be true 4K—the interviews are upscaled from standard HD, and the Trailer and Teasers are both upscaled from even lower resolution sources. (Needless to say, everything is 1080p on the Blu-ray.)

- Masterclass with Walter Hill (14:39)

- Interview with Walter Hill (30:12)

- Alternate Opening Sequence (3:18)

- Original Trailer (2:22)

- Original Teasers (6:54, 13 in all)

The Masterclass with Walter Hill was recorded at the 2022 Clin d’Œil Festival in Reims, France. Hill explains his path from screenwriter to director, as well as his belief in characters being defined by action rather than dialogue, including why he doesn’t like backstories. He admits that he’s not an acting coach, so he relies on having the right screenplay and casting the right actors to develop performances. He also explains his thoughts about film scoring at length, and while he doesn’t mention Small (he focuses Ry Cooder instead), it’s easy to understand why he chose Small for The Driver. He actually doesn’t talk about The Driver at all in this discussion, but it’s still a brief but valuable look at what drives his unique process.

On the other hand, the Interview with Walter Hill was recorded specifically for this edition, so it’s primarily about The Driver. Hill provides the background for the development of the film, including why he chose not to give names to any of the characters. He covers the actors that played them, and defends Ryan O’Neal’s performance from the critics who questioned it. (He also gives an interesting aside about exactly why he had a falling out with Charles Bronson after Hard Times.) He breaks down each of the three major car chases in the film, and talks about his experiences with the genre from having been an assistant director on Bullitt. Interestingly, the main reason why he shot them at night was to do something different than both Bullitt and The French Connection, so that people wouldn’t accuse him of just copying those films. He describes himself as being a selfish filmmaker—he makes movies for himself, and just hopes that people will want to come along for the ride. He closes by giving some interesting thoughts about filmmaking influences—he may indeed have been influenced by Peckinpah, but that’s just the beginning of a chain that leads all the way back to D.W. Griffith, and even Charles Dickens before that.

Finally, the Alternate Opening Sequence was something that 20th Century Fox forced Hill to shoot in order to clarify the relationships between the characters, especially in terms of The Player’s involvement with The Driver, and also supporting actor Matt Clark’s somewhat contentious interplay with The Detective. It was never used for the original theatrical release, although it did eventually show up on the television version. Again, it’s never been part of any director’s cut of The Driver.

Speaking of which, this StudioCanal master is the full 91-minute version of the film that includes an extra dialogue scene between The Driver and The Player, starting at approximately 39:35. That scene wasn’t included in the 89-minute North American theatrical cut, and it wasn’t on the previous Region A Twilight Time Blu-ray from 2013. (It has been included on various Region B Blu-rays, however.) What’s a bit murkier is the supposed existence of a 131-minute rough cut that may have been screened by the American Cinematheque, possibly at The Egyptian, back in 2002. Yet there doesn’t appear to be any hard evidence that such a screening ever happened. Back in 2013, when Twilight Time worked with Hill for their Blu-ray, the late Nick Redman reported that "we spent some time with Walter last week and he confirmed to us that there has never been any longer version of The Driver and that no screening of any additional footage has ever taken place." It’s certainly true that there very likely was a longer assembly cut, and there are a few brief snippets of footage in the trailer that weren’t included in the final cut, but the odds that the Walter Hill of 1978 ever intended The Driver to play at that length are slim indeed.

There’s still no real explanation for the minor difference between the 91-minute and the 89-minute version, but with Hill supervising the restoration work for StudioCanal’s new master, it’s reasonable to assume that he approves of this 91-minute cut. He definitely approved of the restoration itself, and it’s a thing of beauty. Since all of the extras are included on the UHD, it’s safe to order the set even if you don’t have a Region-Free player—and if you’re any kind of a Walter Hill fan, you need to own this set, full stop.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook.)