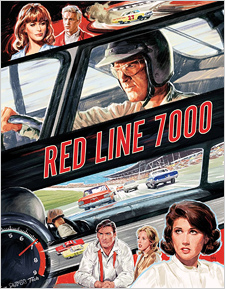

Red Line 7000 (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Howard HawksRelease Date(s)

1965 (July 30, 2024)Studio(s)

Paramount Pictures (Arrow Video)- Film/Program Grade: C+

- Video Grade: B+

- Audio Grade: B

- Extras Grade: B+

Review

While Red Line 7000 has always had its admirers (the critics of Cahiers du Cinéma picked it as one of the ten best films of 1966), it’s generally been regarded as a “lesser” Howard Hawks film. As is sometimes the case, reality lies somewhere in the middle. It’s not a late-period masterpiece like El Dorado, and yet it explores themes that were near and dear to his heart, while simultaneously stretching his storytelling gifts outside of his normal comfort zone. Hawks had been fascinated by racing ever since he was in elementary school, where he first dallied with soapbox cars, and he later toyed with being a professional race driver before he made the fateful decision to work in Hollywood instead. Given his love of professionalism, it was inevitable that he would explore the racing milieu on screen, and it didn’t take him long to do so, either. He made his first racing picture The Crowd Roars in 1932, but while it was moderately successful, he didn’t return to the racing world for more than thirty years. Hawks had aged in the meantime, and as a result, Red Line 7000 is a very different film than The Crowd Roars. Yet it’s still pure Howard Hawks through and through.

Of course, as with any filmmaker who works for as many decades as Hawks did, there’s a definite evolution regarding what constitutes a Howard Hawks film. The theme of professionalism is the anchor that held his entire career together, but as he aged, his style and methodologies relaxed considerably. His earlier films are marked by tightly crafted storylines and rapid fire, overlapping dialogue, but his later work unfolds at a far more leisurely pace. Even his late period westerns like Rio Bravo, El Dorado, and Rio Lobo are really chamber dramas, de-emphasizing the action in favor of having his characters spend most of their time sitting around and chatting instead. There’s less of a clear narrative drive to his later films, too. Yet in general, there’s still a primary arc to these stories, but that’s not the case with Red Line 7000. Hawks didn’t have a single story for the film but rather three different ones, so he decided to have screenwriter George Kirgo help him to tie all of them together. Yet while Hawks had been perfectly comfortable with overlapping dialogue early in his career, he was significantly less comfortable with overlapping storylines, as he explained to Joseph McBride in Hawks on Hawks:

“If you’ve got individual plots like in Red Line 7000, then you’re gone. That movie was no good. I was trying to do something. I tried an experiment. I had three good stories about the race track, but none of them would make a picture, so I thought maybe I can put them together... To be serious, I think there were some pretty good things in it, but as a piece of entertainment, I don’t think I did a good job.”

While many critics at the time agreed with him (outside of France, anyway), Hawks was being far too hard on himself. As other directors like Robert Altman, Alan Rudolph, and Paul Thomas Anderson have proved over and over again, there’s nothing inherently wrong with having interlocking storylines and characters. It was just that Hawks had no experience working in that mode, so he and Kirgo never quite cracked what makes it work. They were far too timid about moving back and forth between the separate storylines, so they let each of them play out individually for longer than necessary, which does negatively impact the overall narrative flow. Crosscutting is the key to making this kind of multilayered storytelling work, and if Hawks had allowed himself further experimentation, he probably would have figured that out eventually.

It doesn’t help that most of the characters in Red Line 7000 feel pretty generic. Casting is everything when it comes to interlocking storylines, as the audience needs distinctive faces that they can latch onto instantly every time that the narrative shifts. Hawks prided himself on his ability to discover new talent like Lauren Bacall, but his eye wavered a bit as he aged. Of the three male leads in Red Line 7000, only James Caan was a noteworthy discovery, with John Robert Crawford and Skip Ward having fallen into obscurity. Most of his female leads fared a bit better, although both Laura Devon and Marianna Hill already had established careers by that point. The one who really got shafted in the deal was Gail Hire, and not only would Red Line 7000 be her one and only film, she only had one other acting credit on the Batman television series before retiring from the business for good. While her inexperience does show at times, and Hawks made the dubious decision to hamstring her by forcing her to speak in an unnaturally low vocal register (what worked for Lauren Bacall didn’t work here), she still had genuine potential that sadly never developed.

The supporting characters in Red Line 7000 fare much better thanks to the presence of actors like Charlene Holt, Norman Alden, Anthony Rogers, and George Takei. (Watch for Robert Donner and Teri Garr in uncredited cameos.) Unsurprisingly, it’s Holt who makes the biggest impression with her seemingly effortless ability to convey inner strength. She had already worked with Hawks on Man’s Favorite Sport?, and she would go on to have her best role for him a couple of years later in El Dorado. Whatever issues that Hawks may have had with the multilayered storytelling in Red Line 7000, his love of strong, independent female characters rings through loud and clear. He loved strong women just as much as he loved professionalism, and in the case of Red Line 7000, the two sometimes intertwine. In fact, that’s the key to appreciating Red Line 7000 as a whole. It’s a racing film where the racing is ultimately secondary. Come for the male racers, but stay for the women who won’t take any of their shit. These ladies are perfectly capable of making it through life on their own terms, and that’s the heart and soul of much of Hawks’ best work as a filmmaker.

Cinematographer Milton Krasner shot Red Line 7000 on 35mm film using spherical lenses, framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. (Most of the second unit racing footage and background plates were shot by second unit director Bruce Kessler instead, although he wasn’t responsible for the stock footage that was also used in the final cut.) This version uses a 1080p master that was supplied by Paramount, with no other information available about it. It’s the same master that Kino Lorber licensed for their 2017 Blu-ray, although Arrow had some additional color grading and digital cleanup performed by R3store Studios in London. Their work paid off, because this is a significant improvement over the Kino disc. The colors are much better saturated, and the overall brightness and contrast levels are more even. The main unit footage that was shot by Krasner is sharp and clear, although the dirt and scratches on the stock footage has been left alone (most of it has always been already present). There are some blemishes during the opening title sequence as well, but those are inherent to the original optical work. The plate photography and second unit racing footage integrates reasonably well. Still, the elephant in the room is the stock footage. Much of it was shot for television in 16mm, so it had to be blown up in order to be cut into the film, and it really stands out like a sore thumb. But that’s Red Line 7000. It is what it is.

Audio is offered in English 1.0 mono LPCM, with optional English SDH subtitles. It’s a solid track, with clear dialogue and little noise or distortion. Nelson Riddle’s somewhat incongruous score sounds as good as it can, although if he was the one responsible for the various attempts at “pop” instrumentals that are heard in the background, they stand out just as badly as the stock footage does. (Seriously, a twangy C&W version of I’ve Been Working on the Railroad was not exactly hip, even during the Sixties.)

Arrow Video’s Limited Edition Blu-ray release of Red Line 7000 comes with a reversible insert featuring new artwork by Sam Hadley on one side and the theatrical poster artwork on the other, as well as a fold-out poster offering both artworks. There’s also a slipcover with the new artwork and a 20-page booklet featuring an essay by Martyn Conterio. The following extras are included, all of them in HD:

- Audio Commentary with Nick Redman and Julie Kirgo

- Bruce Kessler: Man in Motion (45:25)

- A Modern Type of Woman (19:48)

- Gas, Gears, Girls, Guys & Death (36:23)

- Image Gallery (36 in all)

The commentary with Julie Kirgo and the late great Nick Redman was originally recorded for the 2017 Blu-ray from Kino Lorber—their Twilight Time label was still active at that point, but they did this one on the side. They had a good reason for doing so, since Julie is the daughter of screenwriter George Kirgo. She admits up front that it might make the commentary a bit uncomfortable at times, since Hawks was trying to discover new talent while making a film that would play to younger audiences, but with mixed results. Her father knew nothing about car racing and didn’t even drive at that point in his life, but he did his best to bring all of it together. She gives some insights into that writing process, and also some much-needed biographical details about her father. Together, Redman and Kirgo offer some thoughts about the rest of the cast and crew, including Hawk’s failed discoveries like Gail Hire (who they do believe got a raw deal). They also provide some practical information like identifying the footage that was shot by Bruce Kessler, and examine the critical reactions to the film, including Robin Wood’s defense of it.

Speaking of Kessler, Bruce Kessler: Man in Motion is an interview with the man himself, who passed away a month after it was recorded. Since the interview was conducted by Howard S. Berger for his Destructible Man label, it opens up as a confessional, with Berger explaining what Kessler meant to him personally. The rest of the piece intersperses biographical information provided by Berger with Kessler offering his own thoughts. Kessler’s first experience driving was with sprint cars, and when he entered his first race in 1953 at the age of 16, he had to have his mother sign a waiver—which they ended up handing in to none other than Ken Miles! That eventually led to his involvement in the film industry, among other things working as assistants to Billy Wilder on The Apartment and Jerome Robbins/Robert Wise on West Side Story. It was his experiences making the landmark 1962 short The Sound of Speed that led to him working with Hawks on Red Line 7000. He spent a year shooting the second unit footage for the film, and his skills as a driver helped to open doors for him with NASCAR. (It’s also Kessler doubling all of the actors for the in-car camera footage.)

A Modern Type of Woman is a visual essay by Kat Ellinger that examines the nature of the Hawksian woman in Red Line 7000. She notes that the female characters in the film have far more vitality than the male ones do, making it not really a male-driven sports film at all, but rather a story about the women. She quotes from Hawks on Hawks (how can you not?) to help establish Hawks’ views on women, and traces the development of the female characters throughout his career. She also traces the character arcs for all of the leading women in Red Line 7000, demonstrating how they all have more depth than any of the men. They’re all marked by their ability to navigate male spaces with ease, proving that Hawks consistently didn’t let women’s identities be pitched in service to the men around them.

Gas, Girls, Guys & Death is a visual essay by Howard S. Berger and Angela McEntee that offers a full-throated defense of Red Line 7000—Berger says that it’s the film that made his early impressions of Howard Hawks grow up. Berger defends the fact that Hawks was moving away from having a single clear narrative, and he even defends the anonymous nature of the male characters Red Line 7000, since it makes them more believable. The actors are as interchangeable as the drivers that they’re playing, with someone always waiting in the wings to replace them. That’s because they’re really engaging in gladiatorial combat, with death potentially around the next corner.

Taken collectively, this is a solid set of extras that provides a variety of different perspectives in order to illuminate a film that’s worthy of reconsideration. Will it change anyone’s opinion about Red Line 7000? Probably not, but setting aside biases and examining something with fresh eyes is always a challenge. Even if Red Line 7000 really is “lesser” Hawks, It’s still a film that’s worth putting in the extra effort in order to meet it on its own terms. That’s always a worthy goal, so Arrow’s Blu-ray is an excellent place to start.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter, Facebook, and Letterboxd).