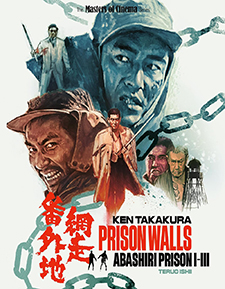

Prison Walls: Abashiri Prison I-III (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Teruo IshiiRelease Date(s)

1965 (June 18, 2024)Studio(s)

Toei Co., Ltd. (Eureka Entertainment)- Film/Program Grade: B+

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: A

- Extras Grade: A

Review

The biggest surprise about Prison Walls: Abashiri Prison I-III (1965) is that it took this long for a western world video label to release it. Considering the international popularity of yakuza films, those from Toei Studios particularly, it seemed odd, at least to me, that these films—some 18 features produced 1965-1972—would be ignored for so long. They’re among the most phenomenally popular movies in the history of Japanese cinema. Consider this: the second, third, and fourth entries all made the list of Top 10 Domestic Films at the Japanese box office in 1965, ranking sixth, fourth, and second, respectively. The following year the fifth, sixth, and seventh films also made the Top Ten, ranking ninth, third, and first place. Compared to, say, Akira Kurosawa’s Red Beard, the top-grossing film of 1965 in Japan but which cost ten times as much, the Abashiri Prison films were inexpensive and thus hugely profitable. They’re the films that solidified Ken Takakura as a top film star and, what’s more, the early ones are especially good—several cuts above the usual Toei yakuza programmer. Prison Walls packs the first three entries onto two discs, supplemented by strong extras.

In the first entry, Abashiri Prison (Abashiri bangaichi, 1965), in black-and-white Toeiscope, a group of newly convicted prisoners—Shinichi Tachibana (Ken Takakura), Gonzo Gonda (Koji Nanbara), and Otsuki (Kunie Tanaka) among them—by train arrive at Abashiri Prison, located near the remote northern coast of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, an area bitterly cold with waist-high snow during winter. The men are assigned a cell with several career criminals, including intimidating Heizo Yoda (Toru Abe) and frail old man Torakichi Akuda (Japanese silent movie star Kanjuro Arashi). At the prison the men do hard labor: cutting down trees in the endless mountain forests, shovel snow, carpentry work and other tasks.

Shinichi’s backstory is revealed gradually, in peeled onion-like flashbacks. His widowed mother is forced to marry a drunken lout for the sake of Shinichi and his sister, but he’s tightwad and abusive. When he can stand it no longer, Shinichi leaves home abruptly, eventually falling in with yakuza who order him to kill a rival boss. This lands him in jail, where he tries to be a model prisoner, encouraged by Tsumaki (Tetsuro Tamba), his parole officer/legal counsel. Shinichi has but six months left on his sentence, but when his mother develops terminal breast cancer, he agonizes over plans by other prisoners to escape. Finally determined to wait out his sentence, he’s nevertheless forced into the escape with snarling Gonda when he jumps out of a moving truck—they’re chained together.

Abashiri Prison began as a 1956 novel by ex-prisoner Hajime Ito. Nikkatsu Studios made a forgotten film version in 1959, directed by Akinori Matsuo and starring Yuji Odaka and Ruriko Asaoka, but it was Teruo Ishii’s film that clicked with audiences. Ishii found the original novel too melodramatic, agreeing to do the film only if he could reshape the last third of the story into a quasi-remake of The Defiant Ones, Stanley Kramer’s film with Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier.

Despite clear echoes of that film, Abashiri Prison is several cuts above the usual Toei yakuza potboiler. Ishii admits he put more effort into that first film than the eight sequels he directed, and it shows. Coming from crackling-good low-budget crime mellers at rival Shintoho in the late 1950s and early ‘60s, Ishii was an early master of black-and-white ‘scope photography. The monochrome lensing (director of photography: Yoshikazu Yamasawa) adds immeasurably to the harsh, snowy environment, something lost on the later films, all the sequels being in color.

Virtually all Japanese movies of the period stuck to stories set in its big cities and, to a lesser extent, nearby rural areas. Hokkaido, because of its distance from Tokyo and harsh weather conditions, is only rarely used as a setting. (Two notable exceptions are Yoji Yamada’s later The Yellow Handkerchief and A Distant Cry from Spring, both starring Ken Takakura playing characters closely resembling his Abashiri Prison character.)

Though overwrought melodrama in one sense, still, even with its exciting Defiant Ones elements, the film is superior to other Toei yakuza stories in subtle ways. It helped redefine Ken Takakura as a brooding but basically decent antihero, famously expressed through the iconic title theme, sung by Takakura himself (its commercial success limited by a ban on performing it on television, due to its “antisocial” lyrics). Though Koji Nanbara is more than a little over-the-top for my tastes, Takakura, Tamba, Tanaka, Abe, and especially Kanjuro Arashi, who has a wonderful, even revelatory scene about two-thirds through the picture, raise the bar.

Abashiri Prison II (Zoku Abashiri bangaichi, or “Abashiri Prison Continues,” 1965) is not at all the sequel one might have imagined. It’s a kind of humorous shaggy dog story in color, without a single moment of its running time set at Abashiri Prison. It also takes place during summer hence no snow. Tachibana (Takakura), having finished his sentence, is aboard a ferry from Hokkaido bound for Aomori with fellow former inmate Otsuki (Joji Ai). There he meets pickpocket Yumi (Michiko Saga), inmate Kirikawa (Kunie Tanaka), en route to confess to an old murder he didn’t commit (he just wants to get out of the prison for a while), and a mysterious Japanese Catholic nun carrying a set of algae moss balls, a popular souvenir from the region. In fact, the nun is acting as a mule for bank robbers smuggling stolen jewels, hidden in the balls.

The nun is murdered and one of the jewel-filled balls inadvertently changes hands several times, eventually winding up in the make-up case belonging to stripper Michiko (Yoko Mihara), mother of a toddler, and whose never-named cuckold trumpet player husband (Shiro Osaka) helps out Michiko’s troupe of exotic dancers. You’d think the paroled Tachibana would want to steer clear of the musical chairs business with the algae ball and the gangsters all trying to get it back, but for no clear reason he allows himself to become neck-deep in this skirmish, eventually leading to former cellmate Yoda (Toru Abe), back with his old gang.

This is a genuinely strange, meandering but entertaining sequel that incorporates many of the characters from the first picture while adding two major female characters. Saga is okay as the incorrigible pickpocket who falls in love with Tachibana, but more memorable than anything else in the picture is cute, flabby Yoko Mihara, onetime Shintoho femme fatale who often worked with director Teruo Ishii there. Completely irresponsible, she leaves her deathly ill toddler in hubby’s care, insisting he take child to the hospital while she visits a gambling den, not only losing all their money in less than two minutes, but so addicted to gambling (while guzzling down sake) that she bets the clothes on her back, ultimately drunk and defeated slumped in a chair with nothing left but her bra and panties. It’s a funny-sad yet truthful scene, if a little out of place in an Abashiri Prison movie.

Further competing with the fatalistic tone of its starkly monochrome predecessor are other comedic scenes including one with Takakura working as a tekiya (disreputable street peddler) like Tora-san, selling women’s underwear, and all the business with Kunie Tanaka’s foolish character, a role concurrent with his “Aodaisho” character, blowhard rival to Yuzo Kayama’s idealized “Young Guy” in Toho’s popular film series.

Abashiri Prison III (Abashiri bangaichi: Bokyohen, or “Abashiri Prison: Saga of Homesickness,” 1965) returns the series to a darker, more fatalistic tone. The presentation opens with a surprising disclaimer from Blu-ray distributor Eureka: “Viewer Warning: This film features a character portrayed by an Asian actor wearing blackface.” While, particularly on Japanese television variety shows, the Japanese have shown great insensitivity in this regard, the “trigger warning” here is rather absurd. The character in question is a mixed-race little girl with a Japanese mother and, presumably, African-American soldier father. (The mother is revealed as a former prostitute.) The character, Emi (Margaret Hayashida) is hardly made up in the denigrating manner of a Sambo-like minstrel, but simply given darker skin and curly black wig. She behaves like a normal kid in the ‘60s Japanese cinema manner, and Takakura’s character is entirely accepting: “Skin color doesn’t matter,” he assures her. In any case, this kind of extreme political correctness is unnecessary and more than a trifle silly.

Shinichi Tachibana (Takakura) travels home to Nagasaki to pay his respects at his mother’s gravesite. After an encounter with Emi, Tachibana becomes embroiled in a waterfront turf war between one gang, led by elderly Asahi (Kanjuro Arashi again) to whom Tachibana owes a debt, and by scheming, smiling cobra Yasui (Toru Abe, each playing different characters from previous entries). Tachibana throws in with Asahi, partly because the aging oyabun wants to go legit, ordering his men, including Tadokoro (Hideo Sunazuka from Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster) and Akira (Kyosuke Machida), to never resort to violence. Yasui, for his part, has ordered tubercular hit man “Killer Joe” Shirayama (Naoki Sugiura) to take out anyone standing in Yasui’s way. When a big unloading job threatens to overwhelm the Asahi-gumi, Tachibana puts a call in to former cellmate Otsuki (Kunie Tanaka) to come to Nagasaki with as many men as he can find.

The film, considered the best of the entire series, has many memorable scenes even though the prison aspects of the original film have all but vanished (other than the title tune), and the picture is really little more than an above average yakuza picture.

Teruo Ishii, however, does a fine job integrating the story with an enormous real local matsuri, the actors mingling among the thousands of spectators, and the requisite face-offs are memorable. In the first, Killer Joe confronts Tachibana about his yakuza past, pointing to a tattoo on his arm. Tachibana responds by casually burning it off with a cigarette lighter, whistling instead of wincing in agony. Their final confrontation is an effective steal from Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz. As before Kanjuro Arashi is given a couple of meaty, amusing scenes, his age and frailty played up much like Zatoichi’s blindness before showing what he’s made of. The scenes between Tachibana and Emi show surprising sensitivity, especially considering how conservative a studio Toei was.

Eureka’s Region “A” encoded Prison Walls: Abashiri Prison I-III is a two-disc set, with the first two films on one disc, the third and various extra features on the second. The 1080p transfers, provided by Toei and all in 2.35:1 Toeiscope, are very good with room for improvement. (Toei, once the leader in high-def transfers of their library titles, seems to have slipped a bit, giving Daiei and Nikkatsu catalog titles the edge; even Toho has improved mightily in the last year.) The LPCM 2.0 mono audio is above average, and the optional English subtitling is excellent.

All three films get brand-new commentary tracks: Tom Mes tackles the first film, Chris Poggiali the second, and Mike Leeder & Arne Venema the third. Two excellent video features are included: Break Out: Jasper Sharp and Mark Schilling Discuss Abashiri Prison and Tony Rayns on Abashiri Prison. Trailers for each film, also subtitled, are included.

A 24-page booklet accompanies the set, with limited credits for each film, poster art, and an excellent essay by Schilling, The Abashiri Prison Series and Teruo Ishii.

For Japanese genre fans this is a must-have. Why did it take so long?

- Stuart Galbraith IV