Phase IV (4K UHD Review)

Director

Saul BassRelease Date(s)

1974 (March 26, 2024)Studio(s)

Paramount Pictures (Vinegar Syndrome)- Film/Program Grade: See Below

- Video Grade: See Below

- Audio Grade: See Below

- Extras Grade: A-

- Overall Grade: A

Review

The Seventies was a unique decade in the development of American cinema, and many of the films that were released during that period are proof of that fact. The collapse of the Motion Picture Production Code during the previous decade provided newfound artistic freedoms, and major studios were actually willing to give filmmakers the money to pursue their own visions. As the decade progressed, the failure of expensive passion projects like New York, New York and Sorcerer resulted in those same studios keeping a tighter grip on the reins, and the implosion of United Artist in the wake of Heaven’s Gate brought the era to a decisive close.

The science fiction genre was no different during the Seventies, with the runaway success of 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968 having opened the doors for filmmakers to pursue grander and more experimental visions of the future and alternate realities. The collapse of the Production code also helped, since many of those visions were far bleaker and more hopeless than anything created during the golden age of Hollywood. Yet it wasn’t failure that ended up reining in this era of fantastic filmmaking, but rather an unprecedented success: the blockbuster release of Star Wars in 1977. Star Wars may have offered a futuristic vision (despite being set a long, long time ago), but the storytelling and stylistic flourishes were of a much simpler and more old-fashioned sort. With occasional exceptions, Star Wars set the tone for the films that followed in its wake.

Yet that doesn’t mean that things were always rosy for visionary filmmakers prior to that point. In 1974, after legendary graphic designer Saul Bass started work on his feature film directorial debut with Phase IV, bad test screenings and nervous executives at Paramount Pictures resulted in his original vision never reaching the screen intact. Yet the final cut that survived is still a unique vision of the birth of a dystopian future, even if just like the ants in the film, the theatrical cut ended up being evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

The basic hook of Phase IV was actually the brainchild of producer Paul Radin, but the idea was fleshed out by Bass and screenwriter Mayo Simon. After an unexplained solar event causes ants to evolve into a sentient collective form, scientist Ernest Hubbs (Nigel Davenport) and mathematician James Lesko (Michael Murphy) set up a research facility in an armored geodesic dome to study the threat that a local colony may pose to humanity. When they attempt to provoke a reaction, the ants respond by attacking a nearby farm, and the sole survivor Kendra (Lynne Frederick) is forced to shelter with them. The facility ends up under siege as well, but the team discovers all too late that while they’ve been studying the ants, the ants have been studying them, and these ants have a master plan.

As initially conceived by Bass and Simon, Phase IV followed in the footsteps of the ending of 2001 by using the techniques of what author Gene Youngblood coined as “expanded cinema” in his 1970 book of the same name. Stanley Kubrick and Douglas Trumbull had used techniques like slit-scan camerawork to create visions that broke with conventional reality and moved into the metaphysical realm, and Bass had similar intentions for Phase IV. The film originally opened with a lengthy, wordless montage that featured abstract imagery of an unexplained astral phenomenon, followed by a visual representation of ants evolving into a higher form of intelligence. Bass also planned an even more elaborate (and equally wordless) ending montage showing the future of mankind under control of the ants, with humanity itself evolving into a different and more subservient form under the watchful eyes of the new overlords.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. Test screenings of the initial cut went poorly, and the original vision that Bass had for Phase IV also began to evolve. Yet this wasn’t a clear-cut case of a studio imposing their own simplistic vision on a reluctant filmmaker, because Bass was actively involved in the process of recutting Phase IV, and he appears to have had his own doubts about what he had created. The first step was the addition of voiceover narration by Michael Murphy that explained what was happening during the opening and ending montages. Eventually, both sequences ended up getting cut down, especially the ending. What survived of that ending the final theatrical cut was a mere shell of what Bass had originally intended, and while the basic concept was still retained, it had lost its heart and soul.

The expanded ending was long thought lost, but in 2012, the original footage was discovered and shown to audiences at the Cinefamily cinematheque in Hollywood after a screening of the theatrical cut of Phase IV. More than a decade later, Vinegar Syndrome undertook the work of trying to recreate the entire preview cut of the film. The results aren’t quite identical to what those preview audiences would have seen, but they’re close. Still, it’s important to remember that the preview cut isn’t a director’s cut in any sense of the term. At best it could be considered a rough cut, because even if Bass had been allowed to retain his original vision for the opening and ending montages, he still would have made changes to the final cut. As it is, he made many small changes throughout the rest of the film that were at his own behest, and there’s a strong possibility that he still would have reshaped the opening and ending montages throughout the rest of the editorial process even if they hadn’t been cut down so drastically.

If “director’s cut” is defined as the director being allowed the freedom to shape his or her own vision all the way through to the end, then there is no director’s cut of Phase IV, there never was one, and there never will be one. The whole experience was traumatic for Bass, and he never even tried to make another feature film again. Yet as unfortunate as that may be, the theatrical and preview cuts of Phase IV provide equally fascinating glimpses into the mind of a filmmaker who wanted to evolve cinema into a higher form, but stumbled before he reached that level thanks to the mundane reality of commercial concerns. The Seventies didn’t end up providing Bass the freedom that he deserved, but both cuts retain enough of his original vision of an alternate plane of existence in order to qualify Phase IV as a landmark in the science fiction genre.

Cinematographer Dick Bush shot Phase IV on 35mm film using spherical lenses, framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. (Ken Middleham’s macro cinematography of the ants was also shot on 35mm film.) This version uses a 4K scan of the original camera negative, digitally cleaned up and graded for High Dynamic Range in HDR10 only. In 4K resolution, many details are now crystal clear, even in the macro photography (it’s amazing how Middleham was able to maintain an accurate plane of focus at that scale with moving subjects). There’s a bit of damage along the right side of the frame in a few shots, but most of the rest of the remaining damage is limited to some light speckling. The only other issues are inherent to the original production. The optical work in Phase IV has always been problematic, so there are still plenty of burned-in blemishes on the dupe elements that were used for those shots. They’ve been left alone here, as they should have been. The HDR grade is more restrained than is typical for Vinegar Syndrome grades, and while a few of the flesh tones arguably still veer a bit too ruddy, everything else looks natural and realistic. Some highlights have been boosted where appropriate, with the rising sun appearing slightly hotter, and the light from the ants’ reflectors looking a little more blinding. Compared to the included Blu-ray version based on the same master, Phase IV isn’t a massive upgrade in 4K, but it’s still demonstrably better.

Audio is offered in English 2.0 mono DTS-HD Master Audio, with optional English SDH subtitles. It’s a clean track, with clear dialogue, and the electronic music is free from distortion. There’s not a lot of depth to the low end, but that’s not particularly surprising.

THEATRICAL CUT (FILM/VIDEO/AUDIO): B/A-/B+

PREVIEW CUT (FILM/VIDEO/AUDIO): B+/B/B

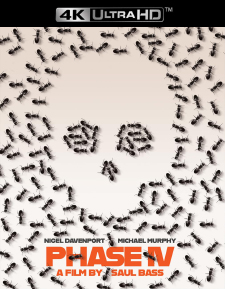

Vinegar Syndrome’s 4K Ultra HD Limited Edition release of Phase IV is a three-disc set that includes the theatrical cut on the UHD and the first BD, with the preview cut on a second BD. (Note that the UHD is Region free, but the BDs are Region A locked.) It’s a slipcase and slipcover combo, with the discs housed in an Amaray case with a reversible insert and a two-sided slipcover. There’s a 10-page booklet tucked inside featuring the storyboards that Bass drew for the ending montage. There’s also a separate 40-page booklet with an invaluable essay by Sean Savage, revised from his original 2014 article for The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists. Everything is housed inside a spot gloss slipcase featuring the new artwork by Adam Maida. Available directly from Vinegar Syndrome, it’s a striking package that’s limited to 8,000 units. (There’s also a standard version available that omits the packaging and the booklets, but the disc-based content is identical.) The following extras are included:

DISC ONE: THEATRICAL CUT (UHD)

- Audio Commentary with Matthew Asprey Gear

DISC TWO: THEATRICAL CUT (BD)

- Audio Commentary with Matthew Asprey Gear

Matthew Asprey Gear is an author, teacher, critic, and lecturer who offers online courses on subjects like Traditions of the Fantastic in Cinema. He opens his commentary by giving an overview of his intentions: to put Phase IV into context with Seventies cinema in general and Seventies science fiction in particular, as well as to provide information about the cast and crew. He opens by going a bit farther back than the Seventies, noting how Phase IV was clearly influenced by the 1905 H.G. Wells short story Empire of the Ants, as well as by The Birds. Gear further establishes the context by tracing the history of other films involving ants in revolt, but explains that one of the main features of science fiction in the Seventies (the first half of it, anyway) was that they didn’t provide any escapism. Gear does cover some details about the production as well, giving special attention to the score, and he discusses the complicated editing process that resulted in the truncated ending.

DISC THREE: PREVIEW CUT (BD)

- Evolutions: The Making of Phase IV (HD – 47:46)

- Formicidae: The Music and Sounds of Phase IV (HD – 14:51)

- Deleted Shots and Sequences (HD – 1:59)

- Raw Footage from Saul Bass’ Original Ending Montage Sequence (HD – 16:34)

- Theatrical Trailer (Upscaled SD – 2:46)

- Still Gallery (HD – 1:31)

Since the original preview print no longer exists in its complete form, this version of the 89-minute preview cut is actually a reconstruction based on the best available elements (the new 4K scans were used where appropriate, with inserts based on dupe elements). The project was supervised by Jeffrey Bass, using Saul Bass’ original editing notes as a guide. The overall picture quality is identical to the Blu-ray of the theatrical cut, with the five minutes worth of added footage exhibiting an understandable drop in quality. There does appear to be a hitch, though. The expanded ending is available elsewhere, and after the final shot of the ant looming over Murphy and Frederick, it cuts immediately to the sun rising over the hills, and “Phase IV” is typed out in the upper right-hand corner of the screen, just like Phase I, II, and III are during the rest of the film. In this version, it fades to black after the final shot, but you can still hear the sound of the wind and the teletype machine. Then it cuts straight to the closing credits from the theatrical cut. Since this is actually a reconstruction of the preview cut rather than a transfer from a full print, it looks like they made a mistake in the process. Supposedly Vinegar Syndrome is aware of the situation, and we’ll update this if they make an announcement about it.

The 2.0 mono DTS-HD Master Audio on this disc is offered with two different options: the London preview soundtrack with no narration, and the later California preview soundtrack with the added Michael Murphy narration. Either way, there are optional English SDH subtitles. (In the commentary track, Gear says that the London cut had the narration and the California cut didn’t, but it’s likely that he simply misspoke.)

Evolutions: The Making of Phase IV is a new three-part documentary by Elijah Drenner that features interviews with Jeffrey Bass, Michael Murphy, Mayo Simon, archivist Sean Savage, and biographer Pat Kirkham. It also includes archival interviews with Saul Bass and producer Paul Radin. Evolutions is more than just a making-of featurette, since it takes its time to establish who Saul Bass was and why his artistic contributions to the cinema were so important. After giving that background, it moves on to what led to the production of Phase IV, and then it details the tortured editorial process, including the rediscovery of the “lost” ending montage. Evolutions also offers an overview of the changes that were made (Simon bluntly acknowledges that the new writing was “essentially kinda lame”), as well as an assessment of the film’s legacy. This is definitely the best starting point for anyone wanting to learn more about Phase IV.

Formicidae is a look at the creation of the electronic music in Phase IV. It’s really a conversation between composers Brian Gascoigne and David Vorhaus, who discuss their own work on the film, and the work of others like Stomu Yamashta, Delia Derbyshire, and Desmond Briscoe. The credits on Phase IV were as complicated as the music, and some of the people who were credited didn’t actually contribute anything to the film. They also explain how some of the music and effects were created, like the sound of the ants, and demonstrate one of the vintage synthesizers that were used.

The Deleted Shots and Sequences is a brief montage of unused footage, most of which was probably used in the original preview version, but it was all too fragmentary to reincorporate in this new reconstruction. It really is brief, too, with many of the shots running a fraction of a second, but it’s still nice to have the footage available. The Raw Footage collection is more significant, since it offers unedited raw footage from the original ending montage, including alternate takes and extended shots that are different than what ended up in the preview cut. Some of it is genuinely raw footage, too, with the opening slates retained. There’s also a Still Gallery and a Trailer.

It’s a fine slate of extras, especially the documentary, but there’s a significant quantity of extras from previous releases that aren’t included. The 2015 Region A Blu-ray from Olive Films was bare-bones, but the Region B releases from Carlotta Films in France, 101 Films in the U.K., and Capelight Pictures in Germany all offered extras that are missing here. That includes a commentary with Allan Bryce and Richard Holliss, the featurette An Ant’s Life: Contextualizing Phase IV, split-screen comparisons, a restoration featurette, and the original ending montage with optional commentary. The biggest omission is that all of these releases included a collection of the Saul Bass short films The Searching Eye, A Series of Explorations, Episodes & Comments on Creativity, Bass on Titles, An Essay: The Popular Arts Today, A Short Film on Solar Energy, and Quest. The omission of the short films huts the most, so you’ll definitely want to hang onto any of those other sets. Yet Vinegar Syndrome’s new 4K master, the reconstructed preview cut, and Evolutions make this an absolutely essential release, so you’re just going to have to make more room on your shelf. Such is the dilemma of collectors during the so-called death of physical media. There are worse problems to have.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook.)