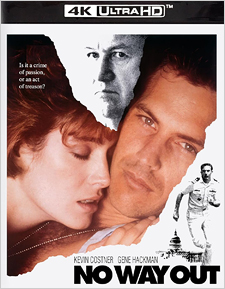

No Way Out (4K UHD Review)

Director

Roger DonaldsonRelease Date(s)

1987 (July 30, 2024)Studio(s)

Orion Pictures (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: B

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: B

- Extras Grade: B

Review

The title of Roger Donaldson’s 1987 sleeper hit No Way Out is the key to unlocking the film, but not necessarily in the expected fashion. Superficially, at least, it seems like an apt description of the situation faced by its protagonist, Lieutenant Commander Tom Farrell (Kevin Costner). His friend Scott Pritchard (Will Patton) is the general counsel to Secretary of Defense David Brice (Gene Hackman), and Pritchard helps Farrell to secure a job with Brice. Meanwhile, Farrell also starts having a relationship with a socialite named Susan Atwell (Sean Young), unaware of the fact that she’s secretly Brice’s mistress. That would be a thorny enough situation for him to navigate, but after a murder takes place in Washington, D.C., Pritchard and Brice enlist Farrell’s help in investigating whether or not a rumored Soviet sleeper agent may have been involved. Farrell agrees despite the fact that he knows that he could end up being implicated for the crime, and since he had nothing to do with it, he actively works to cover up any evidence that could point to him as a suspect. Yet the more that he tries to divert attention away from himself, the more that the evidence keeps piling up. In this Hitchcockian cat-and-mouse game, Farrell isn’t a man wrongly accused, but rather a man who’s unsuccessfully trying to stay one step ahead of being wrongly accused. No way out, indeed.

Yet No Way Out is nowhere near as straightforward as the title might seem to indicate. No Way Out was actually the title of a 1950 film noir directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, but Donaldson’s film isn’t a remake of it. Instead, it’s a loose remake of John Farrow’s 1948 thriller The Big Clock, which was itself an adaptation of the 1946 novel by Kenneth Fearing. Nothing about No Way Out is straightforward, including the title. It’s a story about perceptions, especially false ones, so it’s entirely appropriate the title offers its own sleight-of-hand. It’s a layer that hides the layers that are already hiding layers underneath them. Fearing’s novel did something similar as it cycled through perceptions while it cycled through its chapters. The story was told from the perspective of seven different characters, with each chapter focusing on a single one of them. While the title The Big Clock has a literal reference in the book, it’s also a description of the structure of the story, with perspectives shifting like the hands of a metaphorical clock. Unsurprisingly, that structure ended up being simplified in Farrow’s film, but it returns in Robert Garland’s script for No Way Out—although once again, not necessarily in the expected fashion.

No Way Out opens with Farrell in an interrogation room. His nerves are clearly frayed, he’s smoking compulsively, and there are blood stains on his uniform. He’s being asked how he came to meet Secretary Brice, and then the rest of the story unfolds in flashback. Or so it seems, anyway. There are three primary perspectives in No Way Out: Farrell, Pritchard, and Brice. (Susan might initially seem like a fourth, but she’s only ever seen from the perspective of one of the other three characters.) Yet this is no Rashomon where we’re actually shown events from the point of view of all three characters. Instead, everything is being filtered through the framing device of Farrell’s interrogation session. That’s easy to forget while the film unfolds, but it does add a wrinkle every time that viewers are shown something that occurred while he wasn’t present. This Farrell’s version of events, so we’re not necessarily seeing Pritchard and Brice’s perspectives, but rather Farrell’s perspective on their perspectives. In other words, we may not actually be seeing what’s happening, and Farrell might be an unreliable narrator.

To be fair, it’s unlikely that Donaldson and Garland intended No Way Out to be read that way. Aside from the framing story, there are no other obvious devices like Akira Kurosawa used in Rashomon to indicate that we’re seeing anything but the unvarnished truth. Viewers to tend to accept what they see at face value, as evidenced by the fact that it rarely bothers anyone that the flashback structure chosen by Steven Spielberg and screenwriter Robert Rodat for Saving Private Ryan means that the entire film is a lie (it’s the memories of someone who wasn’t there to witness everything that he’s supposedly remembering). Donaldson and Garland probably intended everything in No Way Out to be taken at face value as well, without having the framing device call any of it into doubt. Yet they’re both responsible for the film’s notorious conclusion, which deliberately upends everything that happened before it. If it’s anything other than a twist ending just for the sake of having a twist ending, then it’s perfectly fair to read No Way Out as a postmodern commentary on the nature of cinematic perspectives. Farrell may or may not be an unreliable narrator, but we can’t necessarily even trust our own perceptions, let alone his. Sometimes, the last layer of deception is our own eyes, and we’re just another set of numbers on the big clock.

Cinematographer John Alcott shot No Way Out on 35mm film using Arriflex 35BL 4 cameras with spherical lenses, framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. This version is based on a 4K scan of the original camera negative, graded in High Dynamic Range for both Dolby Vision and HDR10, but there’s no other information available about the new master. Fortunately, it speaks for itself. The image is refined, beautifully detailed, and immaculately clean, with a fine layer of grain always looks smooth and natural. While Alcott composed for 1.85:1, he still shot everything in the System 35 format that he had pioneered a few years earlier on Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes. System 35 was an early forerunner of Super-35 (it was usually referred to as Super Techniscope when anamorphic release prints were involved). Shooting this way would eventually be referred to as Super 1.85, since it allowed for a larger negative area than standard 35mm. The benefits are obvious here.

Kino has encoded No Way Out on a BD-100 with a healthy bitrate, so there are no compression artifacts of note. The HDR grade is appropriately restrained, with the biggest improvements coming from the contrast range. The highlights aren’t exaggerated, but the blacks are genuinely deep without any crushed detail. There’s a lovely balance in the interiors between the practical light sources, the characters, and the sets that surround them. The warm amber tone in these scenes have been reproduced accurately, while the colors look more uniform in the daylight scenes. In other words, everything looks exactly like it should. It’s a gorgeous transfer.

It’s also a wonderful tribute to John Alcott’s talents. He passed away in 1986 shortly after principal photography had been completed, and he never got to see the finished film. (No Way Out was dedicated to his memory.) Thanks to his outstanding work on films like A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, and The Shining, Alcott is often associated with Stanely Kubrick, but he was equally content to work on exploitation fare like Terror Train, Vice Squad, and The Beastmaster. This beautiful new 4K master of No Way Out does justice to his ability to serve the needs of any given story.

Audio is offered in English 5.1 and 2.0 DTS-HD Master Audio, with optional English subtitles. No Way Out was originally released in Dolby Stereo, and the 5.1 track appears to be a straightforward discrete encoding of the theatrical 4-channel matrixed mix. Practically speaking, there’s little difference between the two. It’s a typical Eighties Dolby Stereo mix, with everything being focused on the front soundstage. Even sound effects like thunder and rain are directed mostly directed toward the front channels, not the surrounds. There’s a definite stereo spread, but many key sound effects are anchored to the center channel instead of panning between the right and left channels. Maurice Jarre’s score is heavily synthesizer-based, and the limitations of Eighties synths means that there’s not much depth to it. Still, it’s all more than sufficient for a story like No Way Out.

Kino Lorber’s 4K Ultra HD release of No Way Out is a two-disc set that includes a Blu-ray with a 1080p copy of the film, as well as a slipcover that duplicates the artwork on the insert. The following extras are included:

DISC ONE: UHD

- Audio Commentary by Roger Donaldson

- Audio Commentary by Steve Mitchell and Richard Brewer

DISC TWO: BD

- Audio Commentary by Roger Donaldson

- Audio Commentary by Steve Mitchell and Richard Brewer

- Roger Donaldson Interview (HD – 37:35)

- Trailer (HD – 1:31)

- The Package Trailer (HD – 2:15)

- Mississippi Burning Trailer (SD – 1:37)

- The War Trailer (SD – 2:58)

- Swing Vote Trailer (HD – 2:33)

- The Bounty Trailer (SD – 2:08)

The archival commentary with Roger Donaldson was originally recorded for the 2016 Shout! Factory Blu-ray release of No Way Out. He offers plenty of praise for the cast and crew, including Costner, Hackman, Alcott, Jarre, and editors William Hoy and Neil Travis. Donaldson still claims that he didn’t know that the script was actually a remake of The Big Clock, which may be true, but he does make a few mistakes elsewhere in the track, like saying that No Way Out was shot in Super-35 and released anamorphic. (Alcott did utilize System 35/Super Techniscope for anamorphic releases like Greystoke, but No Way Out was definitely released flat.) Donaldson also addresses the controversial ending, and notes that preview screenings convinced him that the film was going to be a disaster. (Fortunately, he was wrong about that, too.) There are a few gaps sprinkled throughout the track, but Donaldson still offers plenty of interesting details.

The new commentary pairs filmmaker/historian Steve Mitchell with actor and writer Richard Brewer. (Brewer appeared in Mitchell’s documentary King Cohen.) They start by admitting their affection for Orion Pictures, and then trace the complicated prehistory of the project prior to Orion putting it into production (It was in development for nearly a decade). They offer their own thoughts about the cast and crew, including different angles like Maurice Jarre’s use of synthesizers and Costner’s career trajectory. They also offer some thoughts about the story, and identify some of the subtle clues that are planted throughout the film. They close by describing the critical reactions to No Way Out back in 1987, including reactions to the ending. While they’re guilty of making the standard-issue commentary warning not to listen to it until after you’ve watched the film (something that pretty much no one has ever done), it’s still a great track that complements Donaldson’s own commentary well.

Aside from a collection of trailers, the other new extras is an audio-only interview with Roger Donaldson was conducted by Simon Brew of the Film Stories podcast. It covers similar material to Donaldson’s commentary, including the fact it opens with his denial about knowing it was a remake. Yet Brew keeps things moving at all times, so in some respects the interview plays like a tighter, more focused version of the commentary. They’re both worth listening to, but this is a briefer alternative for anyone who doesn’t have the time for full commentary tracks.

While No Way Out might not seem like the best material for the 4K Ultra HD treatment, looks can be deceiving, on every possible level. Thanks to John Alcott’s superb cinematography, No Way Out looks fantastic in 4K, and it’s equally fantastic that Kino Lorber is willing to give films like this a chance on the format. It’s highly recommended for the beautiful transfer, let alone the solid slate of extras.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter, Facebook, and Letterboxd).