Long Good Friday, The (4K UHD Review)

Director

John MackenzieRelease Date(s)

1980 (May 27, 2024)Studio(s)

Black Lion Films/HandMade Films/Calendar Productions (Arrow Video)- Film/Program Grade: A

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: A-

Review

[Editor's Note: This is Region-Free British import.]

When we first glimpse Harold Shand (Bob Hoskins) in The Long Good Friday, it’s in close-up as he confidently strides through Heathrow airport to the strains of the raucous yet propulsive main theme by composer Francis Monkman. Harold is the king of his world, a gangster who stepped into the void left by the arrest of Ronald and Reginald Kray in 1968, and he’s maintained a tenuous peace in London’s underworld ever since, all while building his own criminal empire—an empire that’s poised to burst into the mainstream thanks to a semi-legitimate real estate deal that he’s putting together with the assistance of the American mafia. When we last see Harold Shand, it’s also in close-up, once again accompanied by the Monkman theme. The difference this time is that we get to watch the confidence slowly drain from his face as it’s replaced first by fear and then eventually by resignation to his fate. Harold has been trying to break into big business, but his fatal flaw is an inability to see the big picture. Douglas Adams once wrote that “if life is going to exist in a Universe of this size, then the one thing it cannot afford to have is a sense of proportion.” That may be true enough on a cosmic scale, but at Harold’s level, failing to understand that there’s always a bigger fish will prove to be his undoing.

In between these two close-ups that (more or less) bookend The Long Good Friday, Harold’s carefully established world order starts to unravel around him, one piece at a time. His closest associate is stabbed to death; another employee is killed by a car bomb that was clearly intended for one of his family members; and a second bomb takes out one of the pubs that he owns, mere seconds before he arrives. Harold sends out his crew (including a briefly-glimpsed Alan Ford) in order to figure out what’s happening and why, while his girlfriend Victoria (Helen Mirren) does her best to smooth things over with the Americans (Eddie Constantine and Stephen Davies). Victoria is the yin to Harold’s yang, a perceptive, intelligent person who can at least take the long view of things, even if she still can’t quite see the whole picture. She’s the real brains of the outfit, a surgical scalpel to Harold’s blunt instrument, but in the end, it’s still not enough when neither of them can understand the nature of the foe that they’re facing.

That’s not surprising, given the convoluted nature of the plot in The Long Good Friday. The film began as a somewhat simpler script by former journalist Barrie Keeffe, who wrote it under a working title that served as a blatant spoiler regarding who’s actually behind everything that’s wrong with Harold’s world. All of that changed during the development process, especially once director John Mackenzie was brought on board. The title was the first thing to go, but the script evolved in many other ways before it finally went in front of the cameras under the aegis of Black Lion, a division of Sir Lew Grade’s ITC Entertainment. (That really was just the beginning of the journey for The Long Good Friday, not the end, but more on that in a moment.) The troubles for Harold begin before he even enters the picture, set up by a complex opening sequence that introduces many of the pieces of the puzzle: Harold’s friend Colin (Paul Freeman); a suitcase filled with money; a double-cross involving that suitcase; a mysterious stranger (Pierce Brosnan, who has a single word of dialogue in the entire film); a dead minicab driver; the minicab driver’s grieving widow (Patti Love); Harold’s trusted lieutenant Jeff (Derek Thompson); a corrupt local politician (Bryan Marshall); and Harold’s tough-as-nails chauffeur Razors (P.H. Moriarty).

Precisely how those pieces fit together is only explained much later in the story, and frankly, it still probably won’t make much sense to a first-time viewer. The Long Good Friday is the kind of film that requires multiple viewings in order to be fully appreciated. The visceral nature of the violence can be apprehended at face value, but the intricacies of the plot require a bit more time and effort to untangle. Full credit for that complexity needs to go to Barrie Keeffe, although John Mackenzie, Bob Hoskins, Helen Mirren, and others had a hand in guiding him during the rewrite process. The Long Good Friday remains his only screenplay that was ever produced as a feature film, but it’s an unabashed corker of a script. However complicated that the details may be, the central irony of The Long Good Friday is that it’s all based on a simple misunderstanding. The fact that Harold ends up taking the blame for something that was set in motion by others only adds to the irony. Even the layers have layers in The Long Good Friday.

Still, much of the credit for the effectiveness of the film as a while needs to go to the towering performance by Bob Hoskins as Harold Shand. The entire cast is superb, with Mirren in particular taking what could have been a thankless role as a gun moll and turning it into something truly special. Yet Hoskins’ performance is one for the ages. If Harold’s fatal flaw is an inability to see the big picture, his deadly sin lies in having the hubris to think that he can solve the troubles on his own terms. He thinks that he’s still in control, but he’s already in over his head, and he doesn’t understand just how big that the other fish really is until it’s far too late. All of that can be read in Hoskins’ face during the close-up that ends the film. It’s not just that you can see what he’s thinking; it’s that you can see exactly how he’s processing those thoughts. It’s one of the greatest final close-ups in film history, rivaling that of Charlie Chapin in City Lights. While the idea for the shot was Mackenzie’s, the execution of it relied on the raw improvisatory talents of Hoskins in order for it to work. He was more than up to the task, and so a star was born—one that burned twice as brightly, for nowhere near long enough.

As obvious as all of that may seem today, ITC had no faith whatsoever in the final cut that John Mackenzie delivered to them. The political angle of the plot made them nervous, and the intensity of the violence was too much for them. They cut the film to ribbons, redubbed all of Hoskins’ dialogue, and planned to sell it directly to television. After a protracted fight, including the threat of a lawsuit, a savior (not the Messiah) appeared in the form of Eric Idle. He encouraged HandMade Films, fresh off their first success with financing Monty Python’s Life of Brian, to acquire the film as a negative pickup at a discount. Of course, HandMade still didn’t make much coin with The Long Good Friday (with rare exceptions, box office success proved consistently elusive for them), but the film garnered positive critical notices and even drew a BAFTA nomination for Hoskins. Most importantly, HandMade saved The Long Good Friday from falling into obscurity. Instead of ending up as a choppy, forgotten telefilm, it’s grown enough in stature over the years to be widely considered as one of the greatest British films of all time. It’s an unforgettable close-up view of one of the most fascinating characters ever to inhabit a gangster film.

Cinematographer Phil Méheux shot The Long Good Friday on 35mm film using Arriflex 35BL and IIC cameras with spherical lenses. Méheux protected the full 1.33:1 frame just in case The Long Good Friday ended up going straight to television, but he always intended it to be matted to 1.85:1 like it is here, and that’s the ratio that was used for the film’s theatrical release. This version is based on a 4K scan of the original camera negative, graded in High Dynamic Range for both Dolby Vision and HDR10. Digital restoration and grading was performed at Sliver Salt Restoration in London, with everything approved by Méheux. (Note that this is the British version of the film, so the title card that was added to international prints in order to explain some of the gangster slang hasn’t been included here.)

The results? Pretty much impeccable. There isn’t a trace of damage remaining, but all of the original grain has been left intact, and it’s handled perfectly by the robust encoding (David Mackenzie at Fidelity in Motion strikes again). The image is stable and solid throughout, with fine detail that’s as well resolved as the negative will allow, and all of the grit that’s still visible is there because it’s meant to be. The expanded contrast range from the HDR grade doesn’t try to reinvent the wheel, and while the black levels still aren’t the deepest, it does help to improve the definition within the brightest highlights. The Long Good Friday hasn’t received consistent color grading over its many previous home video versions, and while I never had the opportunity to see it during its theatrical release in 1981, I wouldn’t presume to trust my own memories anyway. All that I can say is that the grading seems correct here, especially in regards to how it represents the understandably muted colors under the overcast London skies. The reddish flesh tones of earlier releases are gone, replaced by skin that looks much more natural. It’s not bright, it’s not dazzling, but this is reference quality in terms of the way that it preserves the original look of film.

Audio is offered in the original theatrical mix in 1.0 mono LPCM, and a new Dolby Atmos mix that was created at Deluxe Audio in London, based on the original dialogue, music, and effects stems. (Optional English SDH subtitles are also provided.) The original mono mix is reproduced accurately, but it would be a mistake to dismiss the new Atmos track without auditioning it first. It still retains most of the mono character of the dialogue and effects, with occasional steering across the front soundstage like when cars pan across the screen. The surrounds are mostly limited to reverberations and very light ambience. The dialogue is as clear as it can be, although it will always be challenging for American audiences. The biggest beneficiary of the new mix is Francis Monkman’s iconic score, even though it does appear to have originally been recorded and/or mixed in mono. Processed stereo or not, it’s been given more presence in this version. As always, sample both and decide for yourself which one that you prefer.

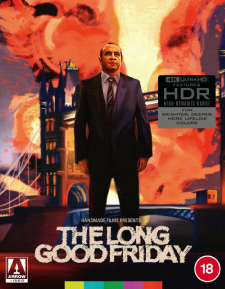

Arrow’s Limited Edition Region-Free 4K Ultra HD release of The Long Good Friday is UHD only—there’s no Blu-ray included in the package. The insert is reversible, with new artwork by Hannah Gillingham on one side and the original theatrical artwork on the other. There’s a foldout poster tucked inside that features the Gillingham artwork only (it’s not double-sided this time). There’s also a 44-page booklet that includes an essay by Mark Duguid; an excerpt from Robert Sellers’ chronicle about HandMade Films, Very Naughty Boys; a selection of excerpts from the original reviews for The Long Good Friday; a Cockney slang glossary; and restoration notes. There are actually two versions of the set available, but the only difference between them is the slipcovers. The standard version utilizes the Gillingham artwork, while the Arrow Store Exclusive version offers the original theatrical artwork. The following extras are included:

- Audio Commentary by John Mackenzie

- Bloody Business: The Making of The Long Good Friday (Upscaled SD – 54:52)

- Interviews:

- Barry Hanson (HD – 5:38)

- Phil Méheux (HD – 3:16)

- Barrie Keeffe (HD – 9:26)

- Simon Hinkly (HD – 18:08)

- Carlotta Barrow (HD – 6:08)

- Hands Across the Ocean (HD – 7:10)

- Q&A with Bob Hoskins and John Mackenzie (Upscaled SD – 27:48)

- Additional Interviews:

- Barry Hanson (HD – 16:14)

- Phil Méheux (HD – 17:35)

- Barrie Keeffe (HD – 14:16)

- Trailers (HD – 4:48, 2 in all)

The commentary with John Mackenzie was originally recorded for the 2002 DVD release of The Long Good Friday from Anchor Bay Entertainment. As soon as the opening credits roll, Mackenzie says that the music takes him back twenty years, and he notes that Francis Monkman had never done a film score prior to that point. Mackenzie does his best to untangle the convoluted plot construction of the film, including how the story evolved over the course of eight different drafts of the script and even during the editorial process as well (he ended up cutting out a far more elaborate opening sequence). He was interested in the political connections in the original draft of the script, but the character of Harold Shand was always the most important thing to him, so he wanted to keep that connection under wraps until later in the film. Mackenzie also offers some interesting technical information, like the complexities of shooting the abattoir scene; how Méheux filmed the moment where a bloody Shand walks off his yacht; the fact that Hoskins ad-libbed much of his last speech; and the way that all of them created the legendary final moment in the car. Mackenzie acknowledges that “It’s quite good, this film,” and he’s right.

Bloody Business: The Making of The Long Good Friday is a documentary that was created for the 2006 Anchor Bay DVD. Covering everything from the development to the release of The Long Good Friday, it features interviews with John Mackenzie, producer Barry Hanson, Phil Méheux, Bob Hoskins, Helen Mirren, and Pierce Brosnan. They also explore how Barrie Keeffe’s original script changed into its final form, including the way that the character of Victoria evolved from being a basic gun moll bimbo into such a central part of Shand’s life. There are some interesting production stories here, like how the car bomb scene was shot in such a way that it allowed the car to explode after the stuntperson entered it without an immediate cut between the two, and much more detail about the troubled post-production period (it wasn’t just HandMade films that saved the picture, but also Bob Hoskins’ ironclad contract). This is probably the best starting point for anyone wanting to learn more about The Long Good Friday.

The various Interviews were produced by Michael Brooke for Arrow’s 2015 Blu-ray release of The Long Good Friday, There were actually two different versions of that release, with only the first three interviews featuring Barry Hanson, Phil Méheux, and Barrie Keeffe appearing on both. Those are briefer ones, with Hanson and Keeffe focusing on Bob Hoskins and the character of Harold Shand, while Méheux offers some details about the remastering process that was completed for that disc. The extended interviews with the same trio were only offered with Arrow’s elaborate six-disc set that included Mona Lisa, as were the interviews with Hinkly and Barrow. The latter two explain their own contributions to the film, while the others cover a wider variety of topics, like how Keeffe drew inspiration for key scenes from his own personal experiences.

Hands Across the Ocean is a comparison of five different scenes from the U.K. version with how they were revoiced (by the original actors) for the international release. It wasn’t so much a matter of the accents as it was that some colloquial expressions were changed into something more easily comprehensible. Finally, the Q&A with Bob Hoskins and John Mackenzie was taped before a 2000 showing of The Long Good Friday at the National Film Theatre in London. They repeat some of the stories about the making of the film and add a few new ones. They also take questions from the audience, including a few curve balls like an accusation about continuity errors that Hoskins answers in character.

That’s nearly all of the extras from both of Arrow’s previous Blu-ray release, save for the 1977 educational short film Apaches that was directed by Mackenzie and shot by Méheux. The only significant thing that’s missing from any previous releases is The HandMade Story, a featurette about the brief history of HandMade Films, that was included on a few different releases overseas. Yet everything else that’s directly related to The Long Good Friday is included here, and while it’s not a huge leap from Arrow’s previous Blu-ray to this new 4K version, the improvements are still clear. This is, without a doubt, the definitive release of The Long Good Friday so far, and probably for the foreseeable future as well. It’s yet another great release from Arrow in a year that’s been filled with great releases. Highly, highly recommended.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook.)