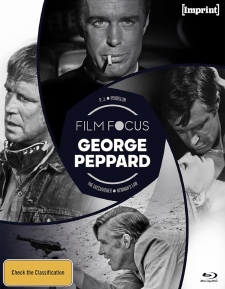

Film Focus: George Peppard (Blu-ray Review)

Director

John Guillermin, George Schaefer, Sam Wanamaker, Richard T. HeffronRelease Date(s)

1968-1974 (September 27, 2023)Studio(s)

Universal Pictures/Columbia Pictures (Imprint/Via Vision)- Film/Program Grade: See Below

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: B-

Review

Actor George Peppard (1928-1994) would seem an odd choice for Imprint’s “Film Focus” series of boxed sets, which thus far has highlighted more obvious actors like Marlon Brando and Gene Hackman. Peppard never achieved anywhere near the level of fame or respect of either of those two talents. His biggest hits, like Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), where carried by other stars; Peppard himself headlined a series of mostly forgotten films in the ‘60s and ‘70s, but is probably remembered by most as the star of The A-Team, the 1983-87 television series.

By his own assessment he was a serious actor, not a star, but was also notoriously difficult, frequently a pain in the ass who damaged his own career battling producers, directors, and even fellow cast members. More than once we walked off the set of a film or TV project, never to return. He was, for instance, the original Blake Carrington on TV’s Dynasty, but so difficult that after filming the pilot he was fired, with all of Peppard’s scenes reshot with replacement John Forsythe. He was a heavy smoker and an alcoholic—the latter reportedly stemming from unhappiness with some of the films in this set—though he stopped drinking in 1978.

On the other hand, in his review of P.J. (1968), critic Roger Ebert said this about Peppard: “He hasn’t been in all that many really great movies, but despite the quality of his material he always seems to salvage a decent performance. And sometimes, when he gets a chance he demonstrates a level of acting ability far above what you usually see from Hollywood.” That’s pretty much correct. Blonde and blue-eyed handsome in his prime, Peppard had many of the same problems as Paul Newman, an actor too good looking to be taken seriously as an actor, and too often pigeonholed in conventional hero parts. Certainly, the film roles that show off Peppard’s talents tend to have him playing a bright, handsome young man struggling with self-doubt, low self-esteem, and disillusionment. In the epic How the West Was Won (1962), Peppard holds his own among the all-star cast, and indeed dominates the story from just before the intermission break, aging from callow youth to disillusioned, hardened ex-lawman.

Imprint’s boxed set offers four little-seen titles: P.J. (1968), Pendulum (1969), The Executioner (1970), and Newman’s Law (1974). All are somewhat interesting, but I didn’t much care for any of them, though The Executioner was much better than I expected it to be.

P.J., seemingly inspired by the success of films like Harper (1964), never really catches fire, though it has its moments. Peppard is private eye P.J. Detweiler, hired by sadistic, penny-pinching millionaire William Orbison (Raymond Burr, his close-cropped hair dyed white, just like his character in Rear Window) as the bodyguard of his mistress, Maureen Preble (Gayle Hunnicutt). Unsurprisingly, she soon favors P.J.’s company in bed to the fat and unpleasant Orbison.

The film introduces various supporting characters: Jason Grenoble (Jason Evers), Orbison’s executive toady; Betty (Coleen Gray), Orbison’s long-suffering wife, whom he enjoys humiliating in public; Shelton Quell (Severn Darden), the Orbison’s flamboyantly gay butler. Eventually the plot moves to a fictitious Caribbean country, but since this is a “nervous ‘A’” with a limited budget, all these scenes are all filmed on Universal’s backlot, augmented by a few Albert Whitlock matte paintings, with soundstage exteriors no more convincing than those found on Gilligan’s Island.

The familiar plot and unsurprising twist near the end don’t help, but the screenplay by Philip Reisman, Jr., he mostly TV writer, has some clever dialogue here and there. Other critics have complained, and I would agree, about the film’s inconsistent tone. Sometimes P.J. is hard-boiled in the manner of Phillip Marlowe, at other times more of a proto-Jim Rockford (always getting beat up), and sometimes the movie teeters on parody.

But it has some good moments, particularly a chase through a Brooklyn subway station, which has a notably gruesome finish. (Location footage in the last third makes a strange contrast to the unreal look elsewhere.) Indeed, the film reflects the new permissiveness following implementation of the MPAA’s rating system. Though mild by today’s standards, 1968 audiences were probably shocked by the relatively graphic violence, as well as its depiction of homosexuality including a gay bar, though it and its customers are about as authentic as the hippies found on Dragnet 1967. There’s even a suggestion of nudity involving Gayle Hunnicutt’s character, she lovely in a ‘60s, big-hair sort of way.

The Raymond Burr character is particularly weird, though Burr’s odd performance is one of the film’s charms. Before playing Perry Mason, Burr literally and figuratively specialized playing heavies. The nine-season run of Perry Mason changed that, yet the actor seems to relish playing this throwback to his early career. Yet, oddly, after all those seasons battling Hamilton Burger in court, with Burr sometimes resorting to teleprompters, Burr’s delivery is almost identical to his tone as the famous attorney. That show ended in 1966 after 271 episodes. From there Burr clearly was lured to Universal, first in the TV movie pilot film for Ironside, and before that series went into production they stuck him in this feature, which opened during Ironside’s first season.

Universal cut corners during this period shooting many of their features in the less expensive Techniscope format. Despite the resultant ‘scope ratio of release prints, director John Guillermin favors a lot of tight, dynamic close-ups and infuses the picture with real energy at times. Film Rating: C

The 2.35:1 widescreen presentation, a 2K scan of the original 2-perf Techniscope camera negative, is pretty solid throughout, if necessarily grainer due to the smaller frame area. The LPCM 2.0 mono is likewise strong, and optional English subtitles are provided. Extras include two audio commentary tracks, a new one by Toby Roan and an apparently older track with Howard S. Berger and Steve Mitchell; also included is a video essay, A Man of Many Phases: The Early Films of John Guillermin, hosted by C. Courtney Joiner. A trailer rounds out the extras.

Like P.J., Pendulum, produced over at Columbia Pictures, is a mixed bag. Anticipating somewhat the neo-fascism of Dirty Harry (1971) and conservative outrage over civil liberties protection for the accused—the Miranda warning having gone into effect in 1966—the film could have been truly fascinating had its screenplay continued in the direction it seems to be heading for most of its running time, instead of opting for the safe, predictable (yet not credible) and uninteresting climax the filmmakers went with.

This time Peppard is Washington, D.C. Police Capt. Frank Matthews, newly appointed consultant for powerful conservative U.S. Senator Cole (Paul McGrath, his performance redubbed by Les Tremayne). At the same time, the conviction of smarmy death row inmate Paul Sanderson (Robert F. Lyons), originally arrested by Matthews, is vacated on a technicality through his liberal activist attorney, Woodrow Wilson King (Richard Kiley).

Meanwhile, at home, Matthews suspects his wife, Adele (Jean Seberg), of cheating on him. She angrily denies it, but Matthews follows her and seems to confirm her affair with an old flame. He feigns an out-of-town business trip, planning to catch her and her lover in the act, and that night Adele and her lover are brutally murdered with shotgun blasts in Matthews’s own bedroom. (Again, rather shocking by 1969 Hollywood standards.)

Naturally, Matthews becomes the chief suspect in the murder, creating much awkwardness with colleagues such as Deputy Chief Hildebrand (Charles McGraw), Lt. Smithson (Frank Marth), Det. “Red” Thornton (Dana Elcar) and others, as well as his new boss in Congress. Matthews ironically turns to lawyer King to defend him.

Pendulum could have been really something. (Spoilers) The screenplay, by producer Stanley Niss, doesn’t show its hand until the climax, suggesting that perhaps Matthews really did murder his wife and her lover, and that all his outrage toward longtime colleagues awkwardly following standard police procedure is just for show, and that King’s steadfast belief in Matthews’s innocence is foolish and naïve. Peppard, for his part, has a better role here, the kind of disillusioned hero he did so well. The supporting cast, however, while good, are typecast down the line. Film Rating: C

In 1.85:1 widescreen, Pendulum looks fine on Blu-ray, and its LPCM 2.0 mono audio (again, with optional English subtitles), is perfectly adequate. No extras here, oddly.

Going in, I didn’t hold out much hope for The Executioner, a late-to-the-party spy thriller made just as that genre was petering out, largely because it was directed by Sam Wanamaker. A blacklisted actor who relocated to England, he directed a handful of feature films, none of them good. His best-known film as director, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977), is notably lifeless, while the movie he made just prior to The Executioner, The File of the Golden Goose (1969), is positively dreadful, one of the worst movies I’ve ever seen. Happily, this one is far better.

John Shay (Peppard) is a London-born but U.S.-raised British MI5 agent nearly killed while on assignment, along with most of his foreign contacts. He suspects fellow agent Adam Booth (Keith Mitchell), the husband of former lover Sarah (Joan Collins), of being a double agent, a Russian Spy. When Shay’s superiors, Col. Scott (Nigel Patrick) and Vaughn Jones (Charles Gray) scoff at the accusation, Shay goes rogue, talking current girlfriend Polly (Judy Geeson), a lower-level MI5 clerk, to steal documents to help prove his case. He travels to Istanbul to question a defecting Russian, Rocovsky (Oskar Homolka), but he’s assassinated before Shay can get much out of him. Later, Shay travels to Athens where he assumes Booth’s identity to meet with CIA agent Parker (Alexander Scourby).

Critics and audiences were divided, most found the film dull and talky, but I agree with the minority that feel the picture has a John la Carré-ish tone, rather than an imitation James Bond one. The unusually intelligent screenplay, adapted from a story by Gordon McDonell, is by Jack Pulman, most famous for this teleplay for I, Claudius, one of the greatest television dramas ever made. The picture also boasts superb cinematography (in 2.35:1 Panavision) by Denys N. Coop (Superman) with especially fine use of locations such as Athens and Corfu, and a fine, brooding musical score by Ron Goodwin (Frenzy).

The best and last film producer Charles H. Schneer made without frequent collaborator Ray Harryhausen, The Executioner and its mostly negative reputation seems more an issue of timing than quality. Had it been released in, say, 1966 instead of 1970, critics might have been more impressed. The cast, which also includes George Baker, Peter Bull, and Peter Dyneley, is excellent, and Peppard is fully engaged in his role.

The transfer, once again, is excellent, the LPCM 2.0 mono (with optional English subtitles) fine (though the dialogue track seems mixed rather low relative to the music/effects track). No extras. Film Rating: B

Newman’s Law is an odd one, originally made as a TV movie by Universal but ultimately released theatrically instead. A French Connection/Dirty Harry-type cop-crime film, by TV movie standards it’s gritty, violent, and generally impressive, but as a theatrical feature it’s just okay.

Los Angeles police detective Sgt. Vince Newman (Peppard) and his African-American partner, Garry (Roger Robinson), arrest drug dealer Jaycee (Teddy Wilson), who in wanting to save his own skin, tips them off about supplier Johnny Dell. Entering Dell’s house, they find his corpse and a motherload of narcotics hidden under the floorboards. The phone rings and when Newman answers, pretending to be Dell, it turns out to be an overseas call from Frank Lo Falcone (Louis Zorich), whom politically ambitious D.A. Jack Eastman (Gordon Pinsent) has been trying to nail for years. Rival mafioso John Dellanzia (Abe Vigoda), Dell’s uncle, offers Newman $10,000 to find his nephew’s killer, but Newman can’t be bought. However, as his investigation into Lo Falcone begins to hint at corruption within the LAPD, Newman is suspended and his friendships, including with partner Garry and his wife (Marlene Clark), are sorely tested.

By TV movie standards, Newman’s Law is quite good. Probably made for around $1.5 million and shot in 20-25 days (so quickly that there are some technical problems; one crucial close shot of Peppard is completely out-of-focus), the film is fast-paced with imaginative coverage by Richard T. Heffron (Futureworld), a good director of tight-budget productions. Particularly impressive, and unusual for something made for network television at the time, is the racial diversity of the cast: Roger Robinson and Teddy Wilson are excellent, and Lo Falcone’s character hires an army of black militant types headed by Mel Stewart, also good. Latin actors are also in prominent parts, including Victor Campos as a young rookie cop. For fans of such things, the film makes excellent use of Los Angeles locations, admirably avoiding overly familiar ones.

At the same time, it’s a little odd watching a 1970s theatrical release so bereft of profanity, graphic violence (by ‘70s movie standards), with no nudity, etc. Probably to ensure a “PG” rating in the U.S., there’s a single shot of Peppard where he calls someone a “dipshit,” a shot that looks like it was retaken at the end of production, inserted to replace an even milder insult. Peppard himself looks like shit. His years of heavy smoking and drinking had caught up with him; he looks disheveled and a little bloated, though his performance is admirably a fully-committed one.

Universal often released their TV movies theatrically overseas, and I imagine the company policy was to frame shots for such films in both 4:3 televisions and 1.85:1 widescreen, whether earmarked for foreign release or not. Newman’s Law reflects this; the framing is never overly-tight and the compositions look good throughout. As noted above, some of the camerawork and lighting is on the rough side, in line with the short production schedule, but it looks no worse than, say, the blaxploitation features of AIP and others. Again, the LPCM 2.0 mono is fine, and supported by optional English subtitles. All four discs are Region-Free. Film Rating: C+

Extras include an audio commentary track by Steve Mitchell and Cyrus Voris, a theatrical trailer and radio spots, and Richard’s Law: The Films of Richard T. Heffron, an interview with director Jeff Burr, who sadly died last October, just as this boxed set was being released. As with Imprint’s Gene Hackman set, I find it odd that none of the featurettes focus on its subject. Shouldn’t something called Film Focus: George Peppard spend some time focusing on... George Peppard?

Film Focus: George Peppard is a somewhat peculiar boxed set. One welcomes the release of such relatively obscure titles, but the movies themselves aren’t all that wonderful, and the extra features are unevenly distributed, though the video transfers are mostly excellent. Not really something for casual viewers but worth a look for “deep dive” film buffs.

- Stuart Galbraith IV