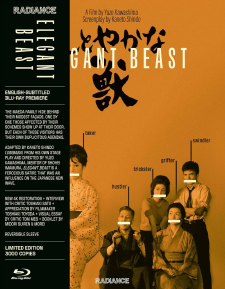

Elegant Beast (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Yūzō KawashimaRelease Date(s)

1962 (December 19, 2023)Studio(s)

Daiei Motion Picture Co., Ltd. (Radiance Films)- Film/Program Grade: A

- Video Grade: A-

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: A

Review

Virtually unknown in the west, Yūzō Kawashima’s Elegant Beast (aka The Graceful Brute, 1962) is a biting satire of Japanese materialism and corruption that really captures the postwar era in which it was made. Written by Kaneto Shindo, another fine director himself, the movie is funny and perceptive, covering a lot of ground in its 96-minute running time. The ensemble cast, headlined by Ayako Wakao, is uniformly excellent, and the setting and structure of the narrative ballsy and unique—virtually the entire film takes place in a cramped, two-room apartment at a huge danchi (typically huge apartment complex).

At this apartment, Tokizo Maeda (Yunosuke Ito) and his wife, Yoshino (Hisano Yamaoka), hurriedly hide various luxuries—television set, a Renoir painting, etc.,—swapping out the luxurious ashtray with a cheap aluminum one from the toilet, and change into shabby clothes. Just as they finish, talent agency owner Ichiro Katori (Hideo Takamatsu), bizarre singing star Pinosaku (Shoichi Ozawa), and Katori’s accountant, Yukie Mitani (Wakao) arrive, Katori demanding that Maeda’s son, Minoru (Manamitsu Kawabata), a bill collector for Katori’s firm, pay the millions of yen he embezzled from the company. Katori needs that money to secure a Japanese tour of American singing sensation “Evelyn Presley,” who commands $50,000/day. Maeda and his wife feign shock and dismay, that their son would never, ever do such a thing. Look around, they say, see our shabby apartment? If he had stolen this money, would we be living like this? The threesome depart.

It soon becomes clear the entire family is blissfully crooked. Not only has Minoru been pocketing payments intended for Katori, he’s also been running up tabs at snack bars charging it to his boss. Meanwhile, the Maeda’s adult daughter, Tomoko (Yuko Hamada), has been soaking a famous novelist, Yoshizawa (Kyu Sazanka), a married man who keeps her as his mistress, her parents virtually pimping her out.

The plot turns on the revelation that Minoru has been siphoning off a significant chunk of his grift to Yukie, the accountant, a single mother using her millions of ill-gotten gain to open a ryokan (traditional Japanese inn) on a prime piece of real estate. Yukie, it turns out, is as coldly-calculating as the Maeda’s are carefree and even likeable. The Maedas have met their match.

Japan in the early 1960s was literally rising from the ashes of its defeat at the end of World War II, when Tokyo and other major cities were firebombed into near-oblivion. Japan’s “economic miracle” hadn’t trickled down to most Japanese, however, who still lived modestly by American standards. Indeed, this was the period when most Japanese coveted the “Three Sacred Treasures”: a television set, a refrigerator, and a washing machine, items an ordinary salaryman would have to scrimp and save for many years to acquire. It was—and still is—a time of widespread corruption: within the various governments, the construction industry and, as seen here, in the entertainment business, where kickbacks and skimming off the top are commonplace.

The brazen thievery of the Maedas must have played like a vicarious dream scenario for Japanese moviegoers at the time. They not only bask in those three sacred treasures, but eat caviar and drink imported whisky, and get to stay at home and relax all day. They may be gaming the system, but they’re also sympathetic; an early monologue by the father, one of the few moments in the film where the audience can take a character at his word, he talks about the wretched poverty he experienced immediately after the war, and how he refuses to ever go back to that kind of life. The self-assuredness and party game-conning of the characters reminds one of Shohei Imamura’s later The Pornographers, Imamura being a direct disciple of Kawashima.

This was Kawashima’s penultimate film, the heavy-drinking filmmaker dying at 45 barely a year after this was made. Beyond the daring use of a single if complex set for virtually the entire film, Kawashima’s direction is notably precise: carefully modulated pacing, interesting lighting and camera angles that express the mindset of various characters, a rationing of close-up, which are always effective when employed, and uniformly excellent performances by all, particularly veteran character actor Ito and star Wakao.

Amusingly, Shindo and Kawashima liken the story like a Noh play, the apartment framed in opening and closing shots like a Noh stage, with Noh music on the soundtrack.

Radiance Films’ Blu-ray of Elegant Beast sources a 4K transfer made by Kadokawa Corp., inheritors of the Daiei film library, with additional color grading done by Radiance. Shot in DaieiScope (2.35:1 anamorphic widescreen), the transfer is very good with maybe a little room for further improvement. (This may be the same transfer as the 2008 Blu-ray in Japan.) The Dolby 2.0 mono audio, Japanese only with optional English subtitles, is good for what it is, and the subtitles are excellent. Encoded for Regions “A” and “B.”

The interesting supplements consist of a 24-page full color-booklet, with good and varied essays by Midori Suiren and Yasunari Takahashi; a video interview with film critic Toshiaki Sato; a visual essay by critic Tom Mes on postwar architecture in Japanese cinema; an appreciation by filmmaker Toshiaki Toyoda; and a Japanese trailer with English subtitles.

I grumble a lot about the fact that too many home video releases of Japanese movies in the west focus almost entirely on genre films (gangster films, chanbara, etc.), so Radiance’s decision to release Elegant Beast, a really superb film that deserves to find a Criterion-level audience, is most welcome. Let’s see more films like this one!

- Stuart Galbraith IV