Conversation, The: Collector's Edition (4K UHD Review)

Director

Francis Ford CoppolaRelease Date(s)

1974 (July 15, 2024)Studio(s)

The Directors Company/Paramount Pictures (StudioCanal)- Film/Program Grade: A+

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A

- Extras Grade: A

- Overall Grade: A+

Review

[Editor's Note: While the 4K Ultra HD disc in this release is Region-Free, the Blu-ray disc is Region B-locked.]

“He’d kill us if he got the chance.”

Those eight words form the lynchpin of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, but not due to any sinister intent that they may (or may not) contain. Instead, they’re the interpretive key to a film that relies heavily on its point of view in order to provide context and meaning. With literature, it’s relatively easy to define whether a work is being written from a first-person or third-person perspective through the choice of language; the use of first-person pronouns like “I” quickly establishes that the story is being filtered through the point of view of its protagonist. With cinema, it’s not quite that simple. While filmmakers like Robert Montgomery, Delmar Daves, and Ilya Naishuller have experimented with using a first-person camera to define perspective, it usually ends up serving as a distancing device instead. Even a first-person voiceover narration acts more as a distancing device than a way of defining a point of view. No, for the effect to work on film, it’s necessary to get viewers inside the head of the protagonist on a less literal level, using more subtle visual and aural cues. The genius of The Conversation is that viewers won’t necessarily recognize that Coppola has been doing just that all throughout the film until those same eight words are repeated near the end—and by then, it’s far too late.

On its surface, The Conversation appears to be an examination of the ethically dubious world of surveillance technology, as well as a meditation on Watergate-era paranoia and conspiracy theories. Yet it’s really a character study, and all of the rest serves to help establish the mental state of its protagonist, Harry Caul (Gene Hackman). Other textural details do so as well, like the fact that Caul is usually seen wearing a thin, translucent plastic raincoat that doesn’t cover him up as much as he thinks that it does. Even the name “Caul” evokes the idea of a thin membrane that doesn’t fully hide what lies within it. In a world that’s built around the processes that are used to reveal hidden secrets, it should be obvious that no one is immune, but Harry’s fatal flaw is that he thinks he should have his own expectation of privacy despite the fact that his entire career is focused on violating the privacy of others. After all, you can’t bug the bugger—or can you?

Harry is the premiere surveillance expert on the West Coast, and as The Conversation opens, he’s doing a job in San Francisco. He’s been hired to record a conversation between Ann (Cindy Williams) and Mark (Frederic Forrest) while they walk around Union Square surrounded by a crowd of bystanders. They chose the location because they thought that they could speak freely without any chance of being recorded, but Harry has figured out a way to cover everything from multiple setups. He has one assistant (Michael Higgins) wandering around the Square with them, and two others poised above with high-powered radio microphones. Meanwhile, his primary assistant Stan (John Cazale) is sitting hidden inside of a van compiling all the recordings and taking surreptitious photographs of the couple. Later, Harry and Stan will use all of these sources in order to mix a single recording that reveals everything. Stan wants to know why their client is after this particular conversation, but Harry rebuffs him:

“It has nothing to do with me, and even less to do with you.”

“It’s curiosity! Did you ever hear of that? It’s just goddamn human nature.”

“Listen, if there’s one sure-fire rule that I have learned in this business is that I don’t know anything about human nature. I don’t know anything about curiosity. That’s not part of what I do.”

Harry Caul operates by this strict professional code, but not out of any sense of moral obligation; rather, it’s nothing but a defense mechanism. Harry has been stung in the past by the ramifications of his work, so his solution has been not to care about anything other than the job at hand—or at least, to pretend not to care. The cloudy morality of the surveillance world seems much simpler when it’s confined to working out the technical issues involved, rather than the nature of what’s being recorded. Harry has decided that the only way to survive is to bury his head in the sand, focus on the process, and ignore everything else:

“I don’t care what they’re talking about. All I want is a nice, fat recording.”

Yet as Harry’s ubiquitous plastic raincoat makes all too clear, his armor isn’t as impenetrable as he thinks that it is. When he attempts to deliver the tape to his unnamed corporate client (Robert Duvall), he’s cornered by the director’s assistant (Harrison Ford) instead. Harry refuses to hand the tape over to anyone but the director, so he locks it up safely in his own workplace. Or so he thinks, anyway; an apparent chance encounter at a convention with another surveillance expert (Alan Garfield) ends up proving that nothing in Harry’s life is as secure as he wants it to be. Of course, he should have already realized that fact, because even his landlady has been able to find a way through some of the locks that Harry uses to protect himself from the outside world.

All of that ends up dialing up Harry’s paranoia over the nature of what’s on the recording. He’s spent his life wracked with tortured Catholic guilt about what happened to the subjects of a previous job, many years ago while he was still working on the East Coast. He’s worried that history might repeat itself, and that ends up clouding his perceptions. Yet for all of the seemingly forensic analyses that Harry has been applying to the Union Square recording, he’s still only listening to it from his own distorted perspective. What’s less obvious on a first viewing of The Conversation is that Coppola and his sound designer Walter Murch have been using subjective audio in order to limit the audience’s perspective as well—we aren’t hearing what Harry hears, but rather what he thinks that he hears. We only discover that we’ve been duped once Harry realizes that he’s misunderstood everything.

The Conversation was partly inspired by Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, but the way that the events in Union Square are broken down is more akin to Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon. The key difference is that rather than seeing different perspectives from different people, we see everything from Harry’s shifting perspectives. He’s the unreliable narrator of his own story, so it’s been a mistake to trust his perceptions about what’s really happening. Those clouded perceptions don’t just apply to what he hears, either, but also to what he sees. As Harry’s mindset deteriorates, there’s no way to know if what we’re seeing is real, or just a figment of his tortured imagination. By the end of the film, his paranoia has induced him to tear his apartment to shreds searching for a hidden recording device, but was he really surveilled, or was that just a paranoid fantasy? Either way, the results are the same for Harry, and his demolished personal space is just an external manifestation of his fragmented mental state. The final overhead camera shot of The Conversation is ostensibly viewing Harry from a third-person perspective, but it’s actually one of the most prefect realizations of a true first-person perspective that’s ever been committed to film, regardless of camera angle. That’s because we’re seeing what Harry feels.

It was all in those eight simple words. We just didn’t realize it at first, because we made the mistake of trusting someone who’s entire life has been defined by deception. We also made the mistake of trusting a filmmaker who works in a medium that’s defined by illusion. The Conversation demonstrates how easily that our own perceptions can be manipulated, and that’s one reason why it’s just as relevant today than in was in 1974. The more that some things change, the more that others stay the same.

Cinematographers Bill Butler and Haskell Wexler shot The Conversation on 35mm film using Panavision cameras with spherical lenses, framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. (Wexler is uncredited in the final film, but he was the original cinematographer and shot the entire opening sequence at Union Square before leaving the project due to his failure to see eye-to-eye with Coppola.) This version is based on a 4K scan of the original camera negative, which is significant because it’s the first time that the negative has been used as a source element for any home video release of The Conversation. Scanning was completed at Roundabout Entertainment in Burbank, and then restoration supervisor James Mockoski took over the digital cleanup work at American Zoetrope in San Francisco. Since the negative hadn’t been overused as much as the ones for Apocalypse Now and The Godfather, the process was much simpler, but plenty of dirt and debris that had to be painstakingly removed on a frame-by-frame basis (no global tools were used, thankfully). The completed restoration was then graded for High Dynamic Range in both Dolby Vision and HDR10 using a print that had been approved by the late Bill Butler as a reference, with Coppola approving the final results.

The opening titles and any transitions like fades or dissolves were obviously sourced from dupe elements instead, and they look a bit softer and grainier than the surrounding material, but there’s nothing to be done about that. (New opticals could be recreated digitally from the negative trims, but they may not even exist anymore, and that would be revisionism anyway.) Everything else is as sharp and detailed as the original lenses and stocks would allow, and it’s immaculately clean, but with all of the original grain intact. StudioCanal has had a mixed track record with encodes in the past, but there are no issues here. The bitrate runs consistently high (not maxed out, but generally in the 70-95mbps range) and the grain never suffers. Even the fog in the dream sequence is handled well.

The new HDR grade may not please everyone equally, but what does these days? The colors are much better saturated here than they were on either the DVD or Blu-ray releases of The Conversation, but they never appear oversaturated. The reality is that the older master(s) looked flat with faded colors, so the improvements to both the colors and the contrast are quite welcome in this case. Some of it may push a little bit into the dreaded orange/teal grading that’s the bane of many modern remasters, but not egregiously so. The reality is that there’s no proof that the older masters were necessarily more correct, and it’s always a mistake to assume that any changes to what’s become familiar must therefore be wrong. Without an unfaded print from 1974 on hand (and even that’s assuming that all prints were timed to Bill Butler’s satisfaction back then), I can’t say what’s the most accurate. I can only say that The Conversation looks outstanding in this rendition, and I’ve never seen it look better.

Audio is offered in English 2.0 mono LPCM, English 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio, German 2.0 stereo LPCM, and German 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio, with optional English SDH and German subtitles. The Conversation was released theatrically in mono only, but the 5.1 remix was created by Walter Murch back in 2000 for Paramount’s DVD version. It does include some added sound effects, although at least a few of them are repurposed effects from elsewhere in the film. For example, there are some added sounds of a dog barking near the beginning of the opening zoom, but it’s a reworked version of the same barking from later on in the same shot when the Doberman appears. On the other hand, sound effects like the electrical arcing of the Muni transit that Harry takes to his girlfriend’s apartment are new.

The mono track here sounds like the original theatrical mix because it doesn’t have any of those added effects, so that may be the best option for anyone who wants to recreate the unaltered experience of seeing the film back in 1974. Here’s the thing, though: Walter Murch is no slouch when it comes to sound mixing. That should go without saying, but keep it in mind before dismissing the 5.1 version without auditioning it first. The reality is that both mixes are superb, and there’s an argument to be made that the subtle immersion of the remix does a better job of placing viewers into Harry Caul’s subjective perspective of the events that happen in the film. The overall fidelity of both tracks is equally superb, and David Shire’s iconic solo piano score sounds equally good, so you can’t go wrong either way. Still, do give each of them a try before you decide one way or the other.

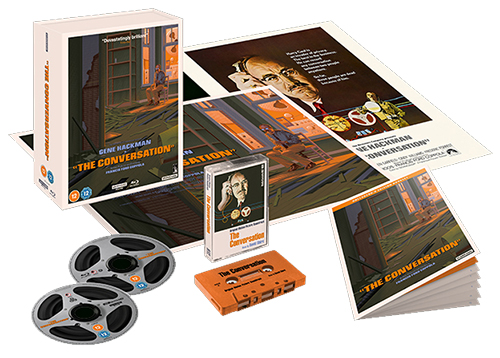

StudioCanal’s Collector’s Edition 4K Ultra HD release of The Conversation is a two-disc set that includes a Region B Blu-ray with a 1080p copy of the film. Both of the discs are imprinted to look like reel-to-reel tape—a nice touch. The new artwork for the packaging was designed by Laurent Durieux, and it includes two foldout posters, one with Durieux’s artwork and the other with the original theatrical poster design. There’s also a 64-page booklet that features essays by Helen O’Hara, David Jenkins, Kim Newman, and Tom Huddleston, plus vintage reviews from Nora Sayre and Stephen Farber. All that, plus an audiocassette copy of David Shire’s soundtrack. Everything is housed inside a rigid case with a magnetic closure. Note that the same extras are available on each disc, but the 50th Anniversary Trailer is in 4K on the UHD while it’s in standard HD on the Blu-ray:

DISCS ONE & TWO: UHD & BD

- Audio Commentary with Francis Ford Coppola

- Audio Commentary with Walter Murch

- Q&A with Walter Murch (HD – 43:28)

- 50th Anniversary Trailer (UHD/HD – 1:00)

- Interview with Gene Hackman (HD – 4:03)

- David Shire Interviewed by Francis Ford Coppola (HD – 10:59)

- Cindy Williams Screen Test (HD – 5:01)

- Harrison Ford Screen Test (HD – 6:43)

- Close-Up on The Conversation (HD – 8:40)

- Coppola Dictates Script:

- Opening Sequence (HD – 2:51)

- The Life of Harry Caul (HD – 2:37)

- The Convention (HD – 4:46)

- Introduction to Frank Lovista (HD – 12:09)

- Jack Tar Hotel (HD – 11:07)

- Police Station Ending (HD – 15:42)

- Harry Caul’s San Francisco: Location Then & Now (HD – 3:42)

- No Cigar (Upscaled SD – 2:28)

- Theatrical Trailer (HD – 2:49)

- Behind-the-Scenes Stills Gallery (HD – 1:55)

The two commentaries were originally recorded for the 2000 DVD release from Paramount. Coppola’s is as much personal memoir as it is a commentary track, tracing the directions that his career took and how The Conversation fit into it. He describes the history of his script, including its influences like Blow Up and the new recording technologies that were becoming available at the time. He wanted to use these ideas to explore repetition from different points of view. He also offers his thoughts about the cast and crew, including his fruitful collaboration with Walter Murch and his less successful one with Haskell Wexler, and explains some of the details like Harry’s infamous plastic raincoat (although he leaves others intentionally unexplained). Coppola does tend to narrate a bit, but he usually elaborates on the themes while he does so.

Walter Murch, on the other hand, gets straight to business and provides much more practical information about the actual making of The Conversation. That includes the first shot of the film, which was photographed using a programmed zoom in order to time it to the exact length needed for the opening titles. Ironically enough given the subject matter, some of the dialogue from the conversation itself was unusable, so Murch took Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest to a different (and quieter) plaza in San Francisco to rerecord them. David Shire’s score was recorded in advance and Coppola played it on set for the actors, just like Sergio Leone had done with Ennio Morricone’s scores, and that also meant Murch had it handy while he was editing. Murch’s commentary is filled with interesting details like that, but he does also offer some thoughts about the story and the characters as well (and when he doesn’t have anything important to say, he doesn’t say anything at all, so there are a few lengthy gaps here and there).

Aside from the 50th Anniversary Trailer, there’s only one new extra: an extended Q&A with Walter Murch that was recorded at a screening of a 35mm print of The Conversation at Curzon Soho in 2017, moderated by Matt Harlock. It’s a great conversation (natch) about everything to do with the film from its conception to its production. Murch explains how the time crunch between The Godfather and The Godfather Part II left him in the lurch when Coppola had to leave to shoot the sequel with 10 pages of the script for The Conversation yet to be filmed. Murch was forced to improvise to figure out how to cut the film around the missing material. He explains some of the differences between the script and the finished film. He also talks about some of his other more recent work like his contribution to recreating the original opening of Touch of Evil the way that Orson Welles intended it to be.

The rest of the extras were originally produced for the previous Blu-ray and DVD releases of The Conversation. There are two different interviews that offer an interesting bookend to each other. The Interview with Gene Hackman was filmed in 1973 on the set of The Conversation for use as part of a promotional reel. It’s included here in its raw form, opening slates and all. David Shire Interviewed by Francis Ford Coppola was taped in 2011 by the director with the composer sitting at a piano, playing some of his themes and talking about his experiences on the film. Shire gives Walter Murch full credit for devising the electronic techniques that were used to distort the sound of the piano as the story progressed.

Two of the original screen tests for The Conversation have been included as well, both of them filmed in 1972. Interestingly enough, neither one of the actors are auditioning for the parts that they would end up playing in the film. Cindy Williams is actually auditioning for the part of Harry’s girlfriend Amy, so it’s the scene where Harry brings the bottle of wine to her apartment. Harrison Ford is auditioning for the part of Mark, with everything filmed “live” in Union Square, so clearly Coppola was also auditioning the techniques that he would use to film the final sequence. Williams plays opposite him as Ann, so either she had already been recast that point or else it was really an audition for both of them. (As much as Ford may be an icon these days, let’s just say that it’s a good thing that Frederic Forrest got the part of Mark instead—he was much better as the sinister assistant.)

Close-Up on The Conversation is the promotional reel from 1973 that ended up using some of the interview footage with Gene Hackman. It includes some actual behind-the-scenes footage from the set, showing how Coppola worked with Hackman to build the character of Harry Caul, and it also shows him working with other actors like Allen Garfield.

Coppola Dictates Script is a collection of Coppola’s original recordings where he dictated the script for his secretary. It contrasts the spoken word with the printed page and appropriate clips from the film. Five different sequences are offered, from the opening one to an unused ending at a police station. Apparently, the latter was filmed but not included in the final cut, and various stills from the sequence are included. It’s interesting, but it would have overcomplicated what’s now a nearly perfect ending as is.

The extras are rounded out with the Theatrical Trailer, a Stills Gallery, and two miscellaneous featurettes. Harry Caul’s San Francisco: Location Then & Now contrasts the San Francisco settings as seen in the film with how they appeared in 2011—the Jack Tar hotel was scheduled for demolition later that year, so it was the last glimpse of that iconic setting. No Cigar has Coppola describing the short film that he made in 1956 and explaining how its central character informed later ones that he created like Harry Caul.

Of course, that’s not actually the end of the extras included in this set, because there’s also the audiocassette copy of David Shire’s soundtrack album:

SIDE A

- Theme from The Conversation (3:30)

- The End of the Day (1:36)

- No More Questions/Phoning the Director (2:16)

- Blues for Harry (Combo) (2:38)

- To the Office/The Elevator (2:37)

- Whatever Was Arranged (2:06)

- The Confessional (2:18)

SIDE B

- Amy’s Theme (2:48)

- Dream Sequence (2:32)

- Plumbing Problem (2:51)

- Harry Carried (2:44)

- The Girl in the Limo (2:23)

- Finale and End Credits (3:52)

- Theme from The Conversation (Ensemble) (2:27)

The idea of offering the soundtrack on audiocassette is a bit gimmicky, but it does make a certain amount of thematic sense. Still, it will be of limited utility to anyone who doesn’t own a cassette deck. I haven’t had one for well over a decade at this point, so I was unable to listen to it (and the running times listed above are pulled from my soundtrack CD, so they may not be 100% accurate compared to the actual cassette).

Of course, the target audience for an elaborate special edition like this one consists of hardcore fans of The Conversation who probably already own the soundtrack, so the cassette is really just another part of the packaging. Taken from that perspective, keeping it in retro analogue format makes perfect sense. It’s a gorgeous set any way that you look at it, and while the new artwork may prove a bit controversial, all artwork proves controversial these days, because we physical media fans always have to find something to complain about. That doesn’t change the fact that this is a fantastic release, with stellar video and audio quality, copious extras, and striking packaging. It’s one of the very best releases of the year so far, and it gets the highest possible recommendation.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter, Facebook, and Letterboxd).