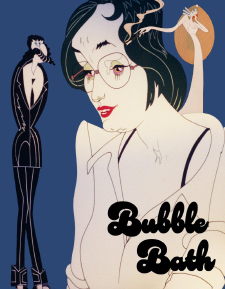

Bubble Bath (Blu-ray Review)

Director

György KovásznaiRelease Date(s)

1980 (March 26, 2024)Studio(s)

Pannónia Filmstúdió (Deaf Crocodile/Vinegar Syndrome)- Film/Program Grade: B+

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: B+

Review

Bubble Bath (aka Habfürdö) was the sole animated feature film from Hungarian artist György Kovásznai, released just three years prior to his death from leukemia at the age of 49. Kovásznai was an author and painter who occasionally dabbled in animation as an alternative means of expression. His abstract form of animation was really an extension of his paintings, employing multimedia techniques like cutouts, live action elements, and even applying paint directly on the frames. The restless nature of this animation style was also an extension of the restless nature of his personal life, a perfect visualization of the turmoil that he felt while living and working in Cold War era Hungary.

Kovásznai had been a student at Budapest College of the Fine Arts during the Fifties, but he left school (repeatedly) without ever graduating. He first dropped out to work as a miner, because he wanted to get a feel for working-class life in Hungary. He had an affinity for the principles of Marxism (although he was uncomfortable with the Hungarian regime), and he wanted to spend some time mingling with the proletariat. When he found that the people couldn’t care less about politics, he returned to school, only to be dismissed for good in 1957. He became a writer and editor for the Hungarian literary journal Nagyvilag, and also held clandestine artistic gatherings at the home of one of his friends, which ended up drawing the attention of the Hungarian authorities. He finally found a real home at Pannónia Filmstúdió in 1961, where he created 25 different experimental animated shorts before his untimely death in 1983. That’s also where he produced his only feature-length foray into the medium, Bubble Bath.

Bubble Bath is a wildly expressionistic musical journey through a Hungarian urban milieu that may bear some stylistic elements in common with George Dunning’s psychedelic Beatles film Yellow Submarine, but it’s subversive in a completely different way. Dunning took the lads on a drug-inspired trip into the alternate reality of Pepperland, but Kovásznai’s subversion lies not in the fact that he employed even more creative artistic techniques, but rather because his characters never leave the city or their otherwise mundane existences. Bubble Bath’s context is more realistic than in Yellow Submarine, but its style is even more psychedelic. Kovásznai utilized every tool in the arsenal that he had been developing in his short films, pushing these techniques to the limit and then beyond. Yet it’s all still in the service of a story that exposes the banality of everyday life, and while his own context may have been limited to Cold War era Hungary, the themes in Bubble Bath are far more universal than that.

Bubble Bath is essentially a musical chamber drama that primarily takes place in a single setting. Zsolt (voiced by Kornél Gelley, but sung by Albert Antalffy) is a window decorator who dreams of doing something more important with his life. He’s engaged to the socialite Klári (Lenke Lorán/Katalin Dobos), who dreams of dropping out of medical school and settling down into a conventional married life. Zsolt is feeling anxiety over being trapped in that kind of domesticity, so he travels to the apartment of medical student Anikó (Vera Venzcel/Kati Bontovits), who happens to be a friend and schoolmate of Klári. Zsolt lacks the courage of his convictions, so he hopes to talk her into delivering a message to Klári that the engagement is off. Anikó dreams of a career as a medical professional, and while she’s not comfortable being the messenger for Zsolt, she realizes that she shares a common bond with him. Yet while they start to feel a mutual attraction toward each other, nothing will end up working out quite the way that anyone in this triangle could have predicted.

Much of the exposition in Bubble Bath is delivered in musical form via songs that were written by János Másik. Animation was a form of expression for György Kovásznai, and music is a form of expression for his characters. Considering that musicals generally provide a form of escapism for their characters, it’s fitting that these characters who dream of something better for themselves use music as their means of escape. Yet none of them ever actually succeed in escaping the mundanity of their modern existences. Kovásznai intersperses their travails with real man-on-the-street audio interviews set to animated form. It’s a reminder that no matter how inventive that his animation may have been, reality is never far behind. Kovásznai expanded the art form to levels that George Dunning never imagined in Yellow Submarine, but he felt no need to create an alternate reality like Pepperland for his characters to inhabit. While he may have discovered early in life that he had no natural affinity for the proletariat, in Bubble Bath, he turned the banality of bourgeois life into the ultimate trip.

Bubble Bath was created via traditional cel animation and photographed on 35mm film by cinematographer Árpád Lossonczy, framed at the full Academy aperture of 1.37:1. This version utilizes a 4K restoration that was performed at the Hungarian Film Lab in 2021 under the aegis of the National Film Institute-Film Archive of Hungary. The original camera negative and a positive print were both scanned at 4K resolution, with digital restoration work also being completed in 4K. Just like the Hungarian Film Lab’s 2019 restoration of Cat City, the image is clean and free of damage, but all of the fine detail, grain, and any artifacts from the animation process have been left intact. Given the multimedia nature of Kovásznai’s animation, there’s plenty of natural texture involved in the paints, paper cutouts, and other three-dimensional elements that were involved. The overall color palette is relatively muted, but there’s still an explosion of different shades on display—a film doesn’t have to be bright and vivid in order to be colorful. Thanks to the usual fine work from David Mackenzie at Fidelity in Motion, everything runs at a consistently high bitrate, and there are no encoding artifacts of note. It’s a nearly flawless presentation.

Audio is offered in Hungarian 2.0 stereo LPCM, with removable English subtitles. Bubble Bath was probably originally released in mono, and the dialogue and sound effects in this restoration are still in mono. On the other hand, János Másik’s music has been expanded to full stereo, and that makes all the difference in the world. There’s a nice amount of clarity in the way that it was mixed, with all of the instruments being clearly defined. While there’s not necessarily much depth to the bass, every note from the bass guitars is clearly delineated and they never sound muddy or ill-defined—something that real bassaholics will appreciate.

The Deaf Crocodile Films Blu-ray release of Bubble Bath is packaged in a clear Amaray case that displays artwork from the film on the reverse side of the insert, which is visible when the case is opened. It also includes a 16-page booklet with an essay by Jennifer Lynde Barker. There’s a spot gloss slipcover available directly from Vinegar Syndrome, limited to the first 2,000 units, that was designed by Alessa Kreger. The following extras are included, all of them in HD:

- Audio Commentary by Samm Deighan

- György Kovásznai Animated Shorts:

- Monológ (12:21)

- Átváltozások (6:43)

- Hullámhosszok (9:48)

- Körúti esték (9:04)

- A 74-es nyár emléke (9:53)

- Interview with János Másik (6:45)

- Restoring Bubble Bath (9:01)

The new commentary is by author and film historian Samm Deighan, who acknowledges up front that she’s excited to be doing a commentary for such an unusually hallucinogenic film that pushes the boundaries of what’s possible with animation. It’s not just stylistically different for an animated film, but thematically different as well—it’s about anxieties over the drab nature of modern life, with all of the characters wanting something more than having to settle down in a standard domestic setting. Deighan provides context regarding Hungarian animation in general and Pannónia Filmstúdió in particular, and notes how filmmakers used abstraction in films like these as a way of getting around the censorship of the day. She also explains some of the influences on the film, and provides biographical information the rest of the crew and the voice actors/singers who were in the cast. While Bubble Bath is fascinating even without knowing any of this background information, it’s much richer when considered in context, so Deighan’s commentary is an invaluable resource in that regard.

Bubble Bath may have been György Kovásznai’s only foray into feature-length animation, but Deaf Crocodile has included five animated shorts that he created between 1963 and 1974. They all appear here courtesy of the National Film Institute-Film Archive of Hungary, which once again performed the digital restoration work. Monológ (aka Monologue) was Kovásznai’s first short, and it’s done in a cutout style that foreshadowed what Terry Gilliam would end up doing for Monty Python’s Flying Circus just a few years later—although Kovásznai fearlessly experimental nature led him to transition into live action before the end. Átváltozások (aka Metamorphosis) was even more experimental, with the entire short consisting of just two faces that continually transform over the course of seven minutes, as a way of outlining the evolving nature of modern art. Hullámhosszok (aka Wavelengths) takes a variety of real radio broadcasts and interprets them visually as abstract painted images—as the opening titles explain, “The creators of this film follow the wavelengths.” Körúti esték (aka Nights in the Boulevard) was a trial run for some of the ideas that Kovásznai would employ in Bubble Bath, intermingling real interviews set to animation with even more stylized musical numbers. Finally, A 74-es nyár emléke (aka A Memory of Summer) lets the music take center stage, with tableaus from a summer night in the city constantly metamorphizing via three-dimensional paints dancing over their surfaces, all set to pseudo-rockabilly music. Despite the fact that it’s set in 1974, it’s really Kovásznai’s abstract vision of the political turmoil of the Prague Spring in 1968, with ominous elements at the margins that spell the end of the temporary liberation of that year.

The Interview with János Másik offers the composer explaining his background with György Kovásznai, and how he came to write the music for Bubble Bath. Kovásznai provided lyrics and pre-production drawings that showed what he intended to do, Másik wrote the songs based on that information, and then his music ended up guiding the actual animation. Restoring Bubble Bath covers both the video and the audio restoration of the film. It includes some of the same interview footage with Másik, as well as interviews with National Film Institute staff members György Ráduly, Eszter Fazekas, and Anna Ida Orosz. There’s some interesting information here, like how they created an infrared dirt map of the film scans in order to guide the digital restoration artists.

It’s a nice slate of extras to accompany this beautiful presentation of Bubble Bath. Deaf Crocodile has been performing an invaluable service by making Eastern Bloc fantasy and animation available to Western audiences. From Alexandr Ptushko classics like Ilya Muromets to unforgettable Czech stop-motion films like The Pied Piper, from Romanian animation like The Son of the Stars to Hungarian animation like Cat City, they’ve been consistently knocking it out of the park with these kinds of releases. Bubble Bath is no exception, and it’s arguably one of the crown jewels in their growing catalogue.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook.)