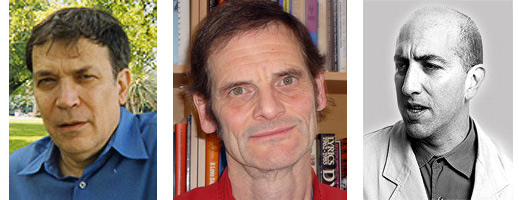

The Q&A participants….

Robert Casillo teaches at the University of Miami and is the author of Gangster Priest: The Italian American Cinema of Martin Scorsese. His other books include The Genealogy of Demons: Anti-Semitism, Fascism, and the Myths of Ezra Pound (Northwestern University Press, 1988), The Empire of Stereotypes: Germaine de Stael and the Idea of Italy (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006) and The Italian in Modernity (co-authored with John Paul Russo; University of Toronto Press, 2011).

Leighton Grist teaches at the University of Winchester and is the author of The Films of Martin Scorsese, 1963-77: Authorship and Context (Palgrave Macmillan, 2000) and The Films of Martin Scorsese, 1978-99: Authorship and Context II (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

Glenn Kenny writes about film for RogerEbert.com and is the author of Anatomy of an Actor: Robert De Niro (Cahiers du Cinema/Phaidon, 2014). He edited A Galaxy Not So Far Away: Writers and Artists on Twenty-Five Years of Star Wars (Holt/Owl, 2002) and was the senior editor and chief film critic of Premiere magazine from 1999 to 2007. He is currently writing a book about the making of GoodFellas.

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): In what way is GoodFellas worthy of celebration on its 25th anniversary?

Robert Casillo: GoodFellas is worthy of celebration upon its 25th anniversary because it is perhaps the best American film to have been made within that span of time. The film also needs to be commemorated because Martin Scorsese is probably the greatest living American film director, and furthermore because GoodFellas is one of his very best, if not the best, of his films. In addition to containing many of his characteristic themes, GoodFellas handles them with remarkable originality, inventiveness, and expressive power. Those themes include that of the endangered subculture which lives by its own distinctive codes and rituals and which finally collapses as a result of conflicts generated from within and outside it. GoodFellas also relies on the characteristically Scorsesean main character, who is at once part of and also somewhat removed from the group in which he finds himself, and whose interstitial position affords him, and through him the viewer, with a detached view of the questionable actions in which he participates. Another point of resemblance between GoodFellas and many of Scorsese’s other films appears in its thoroughgoing elaboration of the theme of the “festival gone wrong,” a phrase which in this case (as in Casino) applies to Mafia festivities resulting in or leading unexpectedly to exclusionary social violence. Again in GoodFellas, as in other of Scorsese’s films, such violence figures within as well as contributing to a larger all-encompassing and escalating rhythm, essentially that of a vortex of violence which, as GoodFellas concludes, accelerates vertiginously out of control. At the same time, Scorsese’s GoodFellas in a characteristically understated way exemplifies the Catholic moral perspective which he reveals in many of his films, and which explains his self-description as a “gangster priest.” And finally, the director’s high level of inspiration in this film must be seen as having an at least partly autobiographical basis, as Henry Hill’s aspiration to join the mob calls to mind the career option once available to Scorsese while growing up in New York’s Little Italy, but which his Catholic scruples, needless to say, led him to reject. Given that the film seems to be so representatively “Scorsesean” in its narrative and use of narration, characterizations, social and dramatic conflicts, focus on the psychology of violence and violent rivalry, tonal variety, irony, point of view, implicit autobiographical resonance, and, not least, ethnic subject matter, to the point of being virtually summative of Scorsese’s directorial vision as a whole, and also given that GoodFellas exploits its materials with a consistent and ever-surprising bravura not to be seen in even the best of most of his other films, it deserves special praise and attention.

Robert Casillo: GoodFellas is worthy of celebration upon its 25th anniversary because it is perhaps the best American film to have been made within that span of time. The film also needs to be commemorated because Martin Scorsese is probably the greatest living American film director, and furthermore because GoodFellas is one of his very best, if not the best, of his films. In addition to containing many of his characteristic themes, GoodFellas handles them with remarkable originality, inventiveness, and expressive power. Those themes include that of the endangered subculture which lives by its own distinctive codes and rituals and which finally collapses as a result of conflicts generated from within and outside it. GoodFellas also relies on the characteristically Scorsesean main character, who is at once part of and also somewhat removed from the group in which he finds himself, and whose interstitial position affords him, and through him the viewer, with a detached view of the questionable actions in which he participates. Another point of resemblance between GoodFellas and many of Scorsese’s other films appears in its thoroughgoing elaboration of the theme of the “festival gone wrong,” a phrase which in this case (as in Casino) applies to Mafia festivities resulting in or leading unexpectedly to exclusionary social violence. Again in GoodFellas, as in other of Scorsese’s films, such violence figures within as well as contributing to a larger all-encompassing and escalating rhythm, essentially that of a vortex of violence which, as GoodFellas concludes, accelerates vertiginously out of control. At the same time, Scorsese’s GoodFellas in a characteristically understated way exemplifies the Catholic moral perspective which he reveals in many of his films, and which explains his self-description as a “gangster priest.” And finally, the director’s high level of inspiration in this film must be seen as having an at least partly autobiographical basis, as Henry Hill’s aspiration to join the mob calls to mind the career option once available to Scorsese while growing up in New York’s Little Italy, but which his Catholic scruples, needless to say, led him to reject. Given that the film seems to be so representatively “Scorsesean” in its narrative and use of narration, characterizations, social and dramatic conflicts, focus on the psychology of violence and violent rivalry, tonal variety, irony, point of view, implicit autobiographical resonance, and, not least, ethnic subject matter, to the point of being virtually summative of Scorsese’s directorial vision as a whole, and also given that GoodFellas exploits its materials with a consistent and ever-surprising bravura not to be seen in even the best of most of his other films, it deserves special praise and attention.

Leighton Grist: GoodFellas is not least worthy of celebration as an exemplary piece of filmmaking, being an exhilarating demonstration of the potentialities of cinema. This is the case not only whether one considers its scripting, performances, cinematography, editing, use of music, or obsessively yet fittingly detailed costuming and production design, but in terms of the nuanced precision of the integration of its constituent stylistic elements with its larger formal and thematic operation. Thematically and ideologically, moreover, GoodFellas constitutes a rigorous critique of the depredations and excesses of American capitalism that, while having pointed relevance to its immediate historical context, continues to resonate to this day.

Leighton Grist: GoodFellas is not least worthy of celebration as an exemplary piece of filmmaking, being an exhilarating demonstration of the potentialities of cinema. This is the case not only whether one considers its scripting, performances, cinematography, editing, use of music, or obsessively yet fittingly detailed costuming and production design, but in terms of the nuanced precision of the integration of its constituent stylistic elements with its larger formal and thematic operation. Thematically and ideologically, moreover, GoodFellas constitutes a rigorous critique of the depredations and excesses of American capitalism that, while having pointed relevance to its immediate historical context, continues to resonate to this day.

Glenn Kenny: These days commemorating movie anniversaries is quite the thing; more often than not it’s got a sort of marketing tie-in, and whatever entity owns the property will re-release a video version; content hungry websites will manufacture the occasion to run “thinkpieces” on the movie... and so on. I myself only CELEBRATE my wedding anniversary; for me GoodFellas is an ever-present part of my cinema sensibility so I don’t need reminding of it. It’s not unlikely that I quote from the movie in my conversation about once a week.

Coate: Can you recall your reaction to the first time you saw GoodFellas?

Casillo: I first saw GoodFellas on its release and was highly impressed. It struck me as Scorsese’s best film since Raging Bull, and very nearly up to the level of that work. My esteem for it has only increased since my first viewing. In my opinion it contains two of the five or six greatest moments in Scorsese, specifically the long tracking shot that leads us into and through the Bamboo Lounge (which we initially believe ourselves to be seeing from Henry Hill’s perspective, through in fact we are not) and even more notably the even longer tracking shot which follows Henry Hill and Karen into the Copacabana. Moments of comparable brilliance in Scorsese’s oeuvre would include the shot of the solitary Jake La Motta shadow boxing at the opening of Raging Bull, La Motta’s rendition of Terry Molloy’s speech from On the Waterfront (at the end of Raging Bull), and the scene in Kundun in which the overhead camera pulls back from the eponymous character of the title to reveal him alone amid an ever widening expanse of slaughtered Buddhist monks.

Grist: I suspect—and it was quite a long time ago!—that my reaction was that GoodFellas was an exciting and considerable motion picture. That noted, as with so much of Martin Scorsese’s filmmaking, the layered, complex coherence of the film came more fully into view upon more reflective consideration, or even upon seeing it more than once.

Kenny: I had met Martin Scorsese for the first time while he was editing the movie, and what he told me about it then made me very eager to see it, so I remember going into the theater—a multiplex on 19th Street and Broadway [in New York City] that I don’t believe still exists—in a high state of anticipation. I felt very, very satisfied as the Sid Vicious version of My Way came on during the end credits. I was reeling—it was a movie that had a real physical impact on me.

Kenny: I had met Martin Scorsese for the first time while he was editing the movie, and what he told me about it then made me very eager to see it, so I remember going into the theater—a multiplex on 19th Street and Broadway [in New York City] that I don’t believe still exists—in a high state of anticipation. I felt very, very satisfied as the Sid Vicious version of My Way came on during the end credits. I was reeling—it was a movie that had a real physical impact on me.

Coate: How is GoodFellas significant within the crime/mobster/gangster genre?

Casillo: GoodFellas is significant within the gangster/mobster genre for having, along with Scorsese’s Mean Streets, helped to give the genre a new orientation and emphasis. At least into the 1970s the gangster film had in a great many instances treated the mob boss as its central preoccupation. One sees this from the very beginning of the sound period, for instance in Hawks’s Scarface, LeRoy’s Little Caesar, and such other thirties films as Marked Woman and Winterset. As for the 1940s, Edward G. Robinson’s fine portrayal of Johnny Rocco (a Lucky Luciano figure) in Huston’s Key Largo, can serve as a representative example, and so far as the 50s are concerned one thinks of Lee J. Cobbs’s portrayal of the mob boss Rico Angelo in Ray’s Party Girl or Rod Steiger as Al Capone in the biopic treating that gangster’s life and career. Consider as well George Raft as the mob boss in Some Like it Hot. In the 60s television drama The Untouchables the mob bosses Capone and Frank Nitti appear prominently, while in the film Johnny Cool (1964) Mark Lawrence plays a Lucky Luciano type. Likewise in Martin Ritt’s The Brotherhood the focus is on an aging and old-fashioned mob boss played by Kirk Douglas, whose supremacy is challenged by his more progressive-minded brother. Even in The Godfather, the chief dramatic interest centers on mob boss Don Vito Corleone and his son and successor Michael Corleone. In virtually every instance, the cinematic mob boss has been a demonic, invidious stereotype, as witness De Palma’s The Untouchables, which appeared shortly before GoodFellas. It can therefore be said that, before Scorsese’s film, no director or scenarist had succeeded in rendering altogether convincingly, and without over-concentration on the figure of the mob boss, the Italian American gangster subculture both in its ethnic dimensions and as a secret society characterized by its own peculiar hierarchies, norms, values, rituals, folkways, etc. Nor had films previous to Scorsese’s done a very good job of conveying the experience of life in the Mafia as seen “from below,” that is, from the point of view of the lower echelons, down in the trenches, so to speak. This is not to deny that, even before Scorsese, some films had attempted to present a more thorough and accurate picture of Mafia society, as witness The  Brotherhood, which does contain some subcultural themes, images, and markers, and which also depicts several scenes in ancestral Sicily. Nonetheless, it was precisely the failure of The Brotherhood to achieve the desired level of authenticity in its portrayal of the Mafia that led Robert Evans, the director of Paramount Studios, the same company that made The Brotherhood, to insist that, in the Paramount production of The Godfather, he wanted to “smell the spaghetti.” By this Evans meant that he wanted to raise the genre of the Mafia film to a hitherto unapproached level of believability in its handling of the Mafia as a specifically ethnic subject. Did Coppola (and Puzo) succeed in doing so? The answer is yes and no. On the one hand, Coppola and Puzo showed their acute sense of the Mafia in its ethnic and social complexity, and also of the interplay between familial and criminal activities. They also avoided the cliché of the psychopathic mob boss driven by sadism and aberrant hypersexuality. Nonetheless, not only does The Godfather fall in line with the majority of its generic precursors in its preoccupation with the mob boss, but it also tends, apparently contrary to Coppola’s stated intentions, to mythify the Mafia—which helps to explain why Don Vito Corleone has entered American folklore. As a special instance of mythification, consider the Robert De Niro sections in Godfather II, which, if looked at closely, seem to come not out of immigrant reality but rather the imagination of Michael Corleone, who transforms his father’s criminal career into the stuff of folk myth. And in Godfather III Coppola and Puzo present an almost entirely stereotyped, mythified, and operatic rendering of the Mafia and even of Sicily itself. Needless to say, it was Coppola’s and Puzo’s aesthetic prerogative to handle their materials as they did, but one may nonetheless complain of The Godfather series that Evans’s hopes of fully smelling the spaghetti were by no means met to the full by Coppola’s choice of using a number of non-Italian American actors in key roles. The casting of Eli Wallach as a mob boss in Godfather III was especially misguided. In any event, the key point as far as Scorsese is concerned is that, in GoodFellas, Scorsese rejects and devastates The Mafia myth through the methods of satire, irony, and black comedy. To use a term that he himself applies to GoodFellas, he offers in this as in his other Mafia films an “anthropological” approach to Italian American criminal organizations. This term alludes in part to his frequently documentary approach in representing the Mafia subculture, which is displayed in the full complexity of its icons, codes, values, and rituals as they bear upon the lives and aspirations of the main characters. Yet the genius of Scorsese also lies in the fact that his documentary impulse never descends to mere exposition or reportage, but is always successfully combined with an expressive and dramatic aim. In contrast with so many earlier films which concentrate on the upper echelons of the mob, GoodFellas presents us with mob as seen from below, through the eyes of its everyday proletarian types. And yet another virtue of GoodFellas is that it many ways it represents a thoroughgoing, that is, fully consistent example of “Italian American cinema” in that all of the roles within the ensemble are taken up by Italian American actors. Although quite a few Mafia films reiterate the older formulas, Scorsese has more than any other director revamped the gangster genre through the example of GoodFellas, which has had wide influence. Newell’s Donnie Brasco, with its lower echelon Mafia characters, and of course The Sopranos come to mind—although I know of no one in this vein who has yet matched GoodFellas for its inventiveness and originality.

Brotherhood, which does contain some subcultural themes, images, and markers, and which also depicts several scenes in ancestral Sicily. Nonetheless, it was precisely the failure of The Brotherhood to achieve the desired level of authenticity in its portrayal of the Mafia that led Robert Evans, the director of Paramount Studios, the same company that made The Brotherhood, to insist that, in the Paramount production of The Godfather, he wanted to “smell the spaghetti.” By this Evans meant that he wanted to raise the genre of the Mafia film to a hitherto unapproached level of believability in its handling of the Mafia as a specifically ethnic subject. Did Coppola (and Puzo) succeed in doing so? The answer is yes and no. On the one hand, Coppola and Puzo showed their acute sense of the Mafia in its ethnic and social complexity, and also of the interplay between familial and criminal activities. They also avoided the cliché of the psychopathic mob boss driven by sadism and aberrant hypersexuality. Nonetheless, not only does The Godfather fall in line with the majority of its generic precursors in its preoccupation with the mob boss, but it also tends, apparently contrary to Coppola’s stated intentions, to mythify the Mafia—which helps to explain why Don Vito Corleone has entered American folklore. As a special instance of mythification, consider the Robert De Niro sections in Godfather II, which, if looked at closely, seem to come not out of immigrant reality but rather the imagination of Michael Corleone, who transforms his father’s criminal career into the stuff of folk myth. And in Godfather III Coppola and Puzo present an almost entirely stereotyped, mythified, and operatic rendering of the Mafia and even of Sicily itself. Needless to say, it was Coppola’s and Puzo’s aesthetic prerogative to handle their materials as they did, but one may nonetheless complain of The Godfather series that Evans’s hopes of fully smelling the spaghetti were by no means met to the full by Coppola’s choice of using a number of non-Italian American actors in key roles. The casting of Eli Wallach as a mob boss in Godfather III was especially misguided. In any event, the key point as far as Scorsese is concerned is that, in GoodFellas, Scorsese rejects and devastates The Mafia myth through the methods of satire, irony, and black comedy. To use a term that he himself applies to GoodFellas, he offers in this as in his other Mafia films an “anthropological” approach to Italian American criminal organizations. This term alludes in part to his frequently documentary approach in representing the Mafia subculture, which is displayed in the full complexity of its icons, codes, values, and rituals as they bear upon the lives and aspirations of the main characters. Yet the genius of Scorsese also lies in the fact that his documentary impulse never descends to mere exposition or reportage, but is always successfully combined with an expressive and dramatic aim. In contrast with so many earlier films which concentrate on the upper echelons of the mob, GoodFellas presents us with mob as seen from below, through the eyes of its everyday proletarian types. And yet another virtue of GoodFellas is that it many ways it represents a thoroughgoing, that is, fully consistent example of “Italian American cinema” in that all of the roles within the ensemble are taken up by Italian American actors. Although quite a few Mafia films reiterate the older formulas, Scorsese has more than any other director revamped the gangster genre through the example of GoodFellas, which has had wide influence. Newell’s Donnie Brasco, with its lower echelon Mafia characters, and of course The Sopranos come to mind—although I know of no one in this vein who has yet matched GoodFellas for its inventiveness and originality.

Grist: The generic significance of GoodFellas is in part historical, in that it comprises arguably the most distinguished film within the noteworthy gangster film cycle that occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and that also included the likes of King of New York, Miller’s Crossing, and The Godfather Part III. Its more specific significance lies in the way that, following Mean Streets, its focus on street-level mob activity compounds the film’s ideological critique in markedly deglamorizing the gangster milieu, this while the film yet conveys, for much of its running time, the on-the-edge rush of lives centered upon constant illicit activity and offers—in a fashion that is, for myself, admirably typical of Scorsese’s filmmaking—representations of working-class masculinity that are unflinching, honest, far from uncritical, but never patronizing.

Kenny: It’s simultaneously the ultimate debunking of the glamorous image of the gangster and a scary summing up of the antisocial license that makes gangsterism look so attractive to alienated “schnooks” everywhere. It very cannily crawls on the razor’s edge of being “irresponsible.” It’s also very frank and scary and lays bare the whole myth of any kind of code of honor among these particular thieves. The highly-charged nature of the filmmaking is incredible: often imitated, never really equaled or replicated.

Coate: Where do you think GoodFellas ranks among Martin Scorsese’s body of work?

Casillo: I would place GoodFellas just after, and close to, Raging Bull among Scorsese’s films. The ultimate difference in quality lies, I believe, in the greater psychological depth and spiritual profundity of the latter film. As one also learns from Scorsese’s biography, he had more invested in its psychologically, and he delivered.

Grist: I’m not much one for rating any films against each other, much less those directed by Martin Scorsese, all of which are, in their often different ways, eminently interesting. However, should my arm be twisted, I would place GoodFellas in the upper echelons of Scorsese’s filmmaking, although it doesn’t reach, to my eyes, the Olympian heights of Taxi Driver and Raging Bull.

Kenny: It’s pretty high in my estimation. Somewhere in the top five.

Coate: Do you believe GoodFellas should have won Best Picture for the 1990 Academy Awards?

Casillo: GoodFellas definitely deserved the Oscar for 1990, though it lost to Dances with Wolves, a now pretty much forgotten Western which does not stand high in the genre. And yet to think that such great Westerns as Ford’s My Darling Clementine, Wagon Master, The Searchers, and The Man who Shot Liberty Valance (all of them favorites of Scorsese) were ignored by the Academy; and what of Hawks’s neglected Rio Bravo, which figures interestingly in Who’s That Knocking at My Door? By this point Scorsese should have won several Oscars for Best Picture, and it is regrettable that the film for which he finally gained the Oscar for Best Picture, The Departed, was a rather ordinary effort.

Grist: Probably, although its not winning was not as great a “crime” as Raging Bull not winning the Best Picture Oscar for 1980. Life is, though, far too short to worry overmuch about the oft-demonstrated critical shortcomings of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Kenny: Yes, I think it should have, but I don’t lose much sleep over the fact that it didn’t.

Coate: Robert De Niro and many of the department heads have worked on several Scorsese films. In what way do these longtime creative collaborations benefit (or hurt) a film such as GoodFellas?

Casillo: I especially admire De Niro’s willingness to participate in a project such as GoodFellas, which required him to reduce his screen-time self-effacingly so as to prevent his obvious star presence from throwing out of kilter the ensemble acting format which is so crucial to the success of GoodFellas, in which the focus is as much on the criminal group as on individual criminals, and in which De Niro’s character is required to figure somewhat subordinately to Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill.

Grist: First, it should be remembered that without Robert De Niro GoodFellas would not exist: lacking the presence of a star of De Niro’s magnitude, Warner Bros. would not have financed the film. It is further testimony to the value of De Niro as a collaborator, as well as to his humility, that, having previously been at least the shared lead in the Scorsese-directed films in which he had appeared, he in GoodFellas took what was a supporting role. Beyond this, it is far from uncommon for directors to work with teams of long-term collaborators, as any glance at the credits of films made by any number of directors will show. In terms of production, the benefits of working with proven and trusted collaborators is obvious: everyone is more or less comfortable with each other, and can be trusted to know the parameters of and expectations that attend their various duties. The clear drawback potential to the repeated use of the same collaborators is staleness, be this in terms of style, subject matter, or approach to that subject matter. Staleness is not, however, anything that GoodFellas could be charged with.

Kenny: I think that having a creative team and crew you can trust, one that goes all out on behalf of the picture, can only ever help. It’s not as if cinematographer Michael Ballhaus or editor Thelma Schoonmaker were going stale when they worked with Scorsese on the picture. Indeed, they were arguably at the height of their powers. There’s always a danger that working with the same people over and over again can induce a kind of complacency but I think particularly here the insane nature of the material pushed everyone to really innovate and react with their most deft artistic muscle.

Coate: What is the legacy of GoodFellas?

Casillo: [As stated earlier in the interview, I would summarize the film’s legacy as:] Scorsese has more than any other director revamped the gangster genre through the example of GoodFellas, which has had wide influence. I know of no one who has yet matched GoodFellas for its inventiveness and originality.

Grist: The legacy of GoodFellas is widely apparent across Western culture. Apart from the quotation of particular scenes and incidents, its stylistic vocabulary has been much appropriated by other films, as well as television programs and advertisements. Unfortunately, such subsequent engagement with GoodFellas has largely tended towards the superficial, with the thematic and ideological critique that the film embodies being too often disregarded. Indeed, if one positive thing could attend the 25th anniversary of GoodFellas, then it would be that people carefully watch and think about the film, which is much more than just the sum of a series of quotable scenes or replicable stylistic components.

Kenny: It’s a really involving movie and still really pertinent; it raised the bar on this kind of genre picture to an extent that is hard to quantify. Yet it is also part of a tradition; it’s a Warner Brothers gangster picture through and through. I think Scorsese knows this, and digs it.

Coate: Thank you, Robert, Leighton and Glenn, for participating and sharing your thoughts on GoodFellas on the occasion of its 25th anniversary.

---

- Michael Coate